The 2019 James Reaney Memorial Lecture was given by Stan Dragland on November 2, 2019 at Wordsfest in London, Ontario.

Below is the full version of Stan Dragland’s lecture and some of the images he used. A list of works cited and notes on the images that accompanied the lecture appear at the end.

James Reaney on the grid

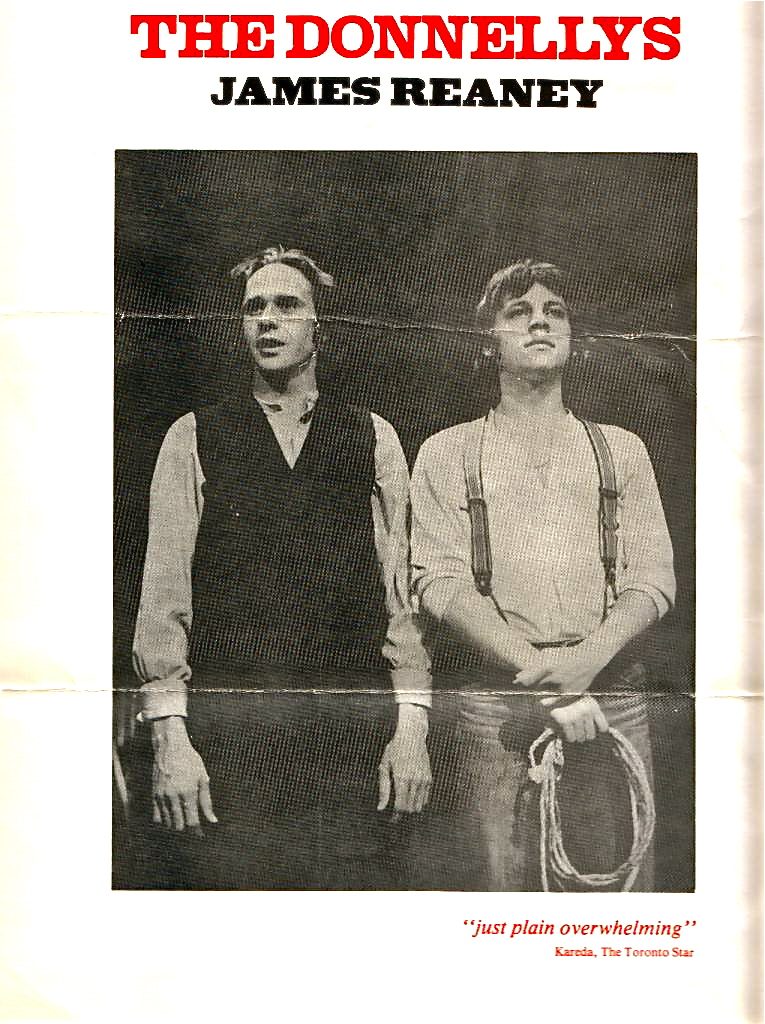

Back in 1970, when I arrived at Western to take up a post in English, I was assigned to English 138, a team-taught, James Reaney-designed course, called Canadian Literature and Culture. Much could be said about the content and delivery of this course, heavy in Southwestern Ontario Literature as it was, but I want to mention just one of our Souwesto books, Orlo Miller’s The Donnellys Must Die. This is a balanced account of the feud along the Roman Line out of Lucan, Biddulph Township, just north of London, that led to the February 1880 massacre of five members of the Donnelly family. Miller’s book is an answer to Thomas P. Kelley’s The Black Donnellys, which has the Donnelly family as a group of low-life, pretty much sub-human cutthroats who terrorized the Lucan area until vigilante members of the community got fed up and took revenge.

One feature of course preparation for English 138 was field trips to locations in our books. On what had been the Donnelly family farm I took a photo of James Reaney holding up two fistfuls of soil. “This is what they were fighting for,” he said, echoing James Donnelly in Sticks & Stonesabout “this Earth in my hand, the earth of my farm/ That I fought for and was smashed and burnt for.”1 Standing with Reaney on the Donnelly property, I didn’t know that I was at ground zero of the creation of a masterpiece, but I found out soon enough. The original idea was to make one play out of the Donnelly material, but the full story was too complex to tell in a single evening; eventually it took three: Sticks & Stones, The St. Nicholas Hotel, and Handcuffs. I saw each of the plays in Toronto. At the beginning of their national tour, September of 1975, I saw them all in a week at Western, in the Drama Workshop in University College. Then, at the finale of the national tour, in what might well have been the opportunity of a lifetime, I saw the whole trilogy in a single day at Bathurst United Church Theatre in Toronto. I was at the climax, though by no means the end, of Reaney’s prolific artistic career. The Donnellys is a tragedy nothing like any of Shakespeare’s, but it belongs in such company.

Now let’s leap to 1984 and an event called the “long-liner’s” conference on the Canadian long poem. Reaney had been listening to various papers on the long poem and indulging in his habit of sketching while others talked; to the published proceedings he contributed quick studies of other presenters. Some of the papers were based on what was called the absence of contemporary “grids of meaning” sponsored by then current post-structuralist theory and embraced by certain postmodernist writers. A presentation by Roy Miki, for example, cited Jacques Derrida on the disappearance of the “transcendental signifier” which had once held everything together. This was part of the orthodoxy of the time, but Reaney was never orthodox, and he wasn’t having it. In his own talk he says “there has to be something outside ourselves that inspires and orders.”2

Reaney’s presentation was so far out of the mainstream of skeptical thought being generally advanced at the time that he could actually call Alligator Pie Dennis Lee’s “most effective poem.”3 Dennis Lee was listening, somewhat ruefully I imagine, since the praise promoted a collection of lyrics into a long poem and whizzed over his adult poetry, including Civil Elegies, which we had taught in English 138. I see Reaney, properly in that company of long poem writers and theorists but not of them, standing for a vision that some of the others will have considered old-fashioned. I’ve become most interested in something he said in the discussion that followed his presentation. Asked where he stood on the matter of those so-called long-gone “grids of meaning,” he offered this take on Derrida: “The way I read Derrida is different. What Derrida is doing is he wants a reaction. He doesn’t want you to agree with him, surely. No one could agree with that! [Laughter] It’s intended to arouse the old, whatever it is—the old Martin Luther, or something, or Ezekiel, or Isaiah, or those Old Testament prophet kinds of thing. Sure the role is absolutely all illusion. Nothing means anything; it’s just a fog. But, by God, I’m not a fog. I see a living chariot with four wheels on it all covered with eyes! How about that?”

(see Open Letter, page 187)

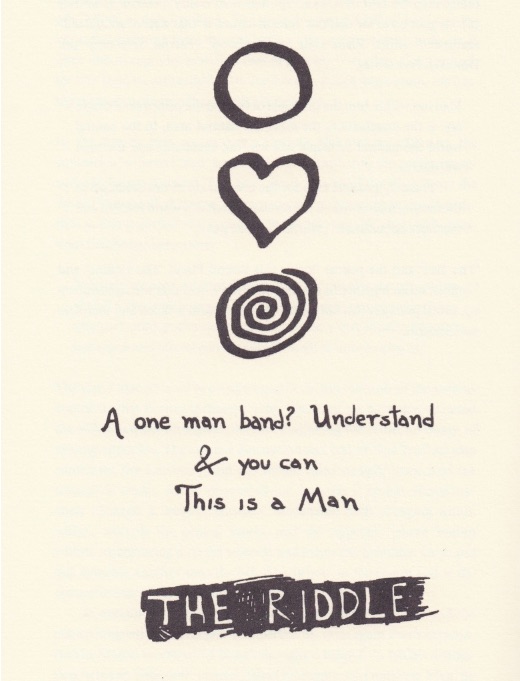

Laughter followed that outburst too, but Jamie was not joking. Suddenly he was Ezekiel, and I’m grateful to Tom Gerry’s book on Reaney’s emblem poems for reminding me that, in this Reaney moment, Ezekiel would be joined by William Blake and Northrop Frye, who says “Blake’s cosmology, of which the symbol is Ezekiel’s vision of the chariot of God with its ‘wheels within wheels’ is a revolutionary vision of the universe transformed by the creative imagination into a human shape. This cosmology is . . . not a vision of things as they are ordered but of things as they could be ordered.”4

“[T] he way Derrida works for me,” Reaney went on as himself, “is that I merely react—not necessarily in a positive, optimistic way, but with images and metaphors; and to hell with it, I don’t care whether they’re ‘grids of meaning’ or not; I’m going to grid away. . . . It makes me happy.”5 His way was to draw material from the local and particular to link it, and so clarify it, with archetypal patterns. He was with William Blake in wanting the New Jerusalem to be established, not only in England’s green and pleasant land, but in Canada, especially in Souwesto, the territory he knew best and loved most. “The most exciting thing about this century,” he says, launching his little magazine, Alphabet, “Is the number of poems that cannot be understood unless the reader quite reorganizes his way of looking at things or ‘rouses his faculties’ as Blake would say. Finnegans Wake and Dylan Thomas’ ‘Altarwise by owl-light’ sonnet sequence are good examples here. These works cannot be enjoyed to anywhere near their fullest unless one rouses one’s heart, belly and mind to grasp their secret alphabet or iconography or language of symbols and myths. A grasping such as is involved here leads to a more powerful inner life, or Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’s Wall.’ Besides which it’s a hell of a lot of fun. It seems quite natural, then, in this century and particularly in this country, which could stand some more Jerusalem’s Wall, that there should be a journal of some sort devoted to iconography.”6

For Reaney, Jerusalem’s Wall is a metaphor for a standing, permanent value, a standard of meaning, and an imaginative approach to making meaning. Reaney is not a biblical literalist. All of his work is pushing for as much New Jerusalem as can be established in this polite, prudish, provincial place. At least that’s how Souwesto and Canada looked to Reaney when he began writing. Here is a simpler way of putting what he was working towards, something he says in 14 Barrels From Sea to Sea, his book about the national tour of The Donnellys: “I wonder if there’s some special firewater you could feed to people in this country just to get a more loving feeling started.”7

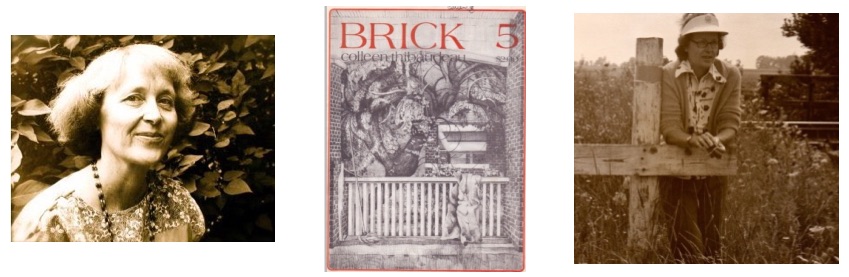

In a minute, I want to show what Reaney was gridding away with. But first it might be well to say that, theory of any kind aside, there are other legitimate and productive ways to work. The handiest and best example I can think of is another of the finest poets ever to write in Canada. I mean Colleen Thibaudeau, who happened to be married to James Reaney. Same household, same politics; very different poetics. Here is Colleen talking about Jamie’s grid work and respectfully distancing herself from it. This is from a special Thibaudeau issue of Brick, part of Jean McKay’s “biographical sketch” of the poet which incorporates an interview with Colleen by Jean, Don McKay, Peggy Roffey and myself: “People were always asking me about the archetypes and things,” says Colleen. “Well, I never studied the archetypes, and they’re a little bit mentally beyond me. I mean if someone explains it to me I can remember it for a while, but I can’t work that way. Like he [Reaney] will draw it all out, and he knows from which column he’s drawing his images . . . and I think that’s good, to be conscious of what you’re doing, but with me they seem to come instinctively from the right area, or . . . It certainly expands your world. . . . It always gives you pegs on which to hang your thought. It makes your mind tidier, and so on. . . .8

In 1957, writing in an essay called “The Canadian Poet’s Predicament,” Reaney seemed to be divided between the two approaches to writing manifest in the household at 276 Huron Street, London, Ontario: the instinctive or the conscious. “No one seems to know, no one seems to be able to tell you, whether you should be self-conscious or unconscious about the craft of poetry, whether you should tackle literary criticism as a help or intuitively arrive at the same goal.” Reading that today, I’m inclined to respond, of course no one knowswhich way to go, because there isno one way. I also wonder about that “should.” Reaney eventually accepted the external authority of Northrop Frye, but not because Frye said anything about what he should do. One chooses, if one feels the need to, on the basis of what and who one is and needs to become. The authority is oneself, in other words. Whatever you do, however you do it, you have to be true to yourself. “[T]he pupil has to fend for himself to honor the professor,”9 writes Guy Birchard, truly. Reaney fended; so did Thibaudeau. End of story.

If this were a Thibaudeau lecture, I’d go on from here to demonstrate why Colleen is much more diffident about her own process than she needs to be. As a poet, she is at least her husband’s equal. I identify with her stance, in fact, because I too have an untidy mind. I come at Reaney from something of a distance myself. But there’s no need to take sides. No matter how anyone works, whether by instinct or according to plan, results are what counts. If Reaney wasn’t getting results, we wouldn’t be honouring him here today. Jean McKay and I, at Brick magazine, admired both Thibaudeau andReaney. Brick 5 was the Thibaudeau issue. Brick 8 was the text for Reaney’s play, King Whistle!, with all sorts of context for the play, including an explanatory essay by the author. Brick Books was equally impartial, though we didn’t become Reaney’s publisher until 2005, when we brought out his last book of poems, Souwesto Home. By contrast, Colleen Thibaudeau’s 10 Letters was the first, in 1974, of what became Brick Books, and we published two other Thibaudeaus thereafter, The Martha Landscapes (1984) and The Artemesia Book (1991), the latter being a selected.

What about the grids? “Grid” is not Reaney’s own word, of course. He picked it up from others at the longliner’s conference, and the literal meaning, with all those right angles, is not the best image for what he does. He’d be more likely to say pattern, or formula, or catalogue, or paradigm, or list. Also backbone. I’ll keep on with grid here, but really list is the better word. “There is something about lists that hypnotizes me,” Reaney says, introducing the “Catalogue Poems” section of Performance Poems. Now watch how he slides disparate things together in metaphor as he goes on: “I think this fascination is connected with our joy in the rainbow’s week of colours, in the 92 element candle you see in a physics lab at school, but then see all around you like a segmented serpent we’re all tied together by. Our backbones, with their xylophone vertebrae, are such sentences; lists of symbolic objects in some sort of mysterious, overwhelming progression I have elsewhere called the backbones of whales, and indeed they are, for they are capable of becoming a paradigm . . . used as a secret structure.”10 His play, Canada Dash, Canada Dotis built on lists of various sorts. So is Colours in the Dark. In fact lists or catalogues are everywhere in his work.

As you can tell from listening to Reaney’s turn as Ezekiel, and this is confirmed by a reading through his work, the Bible was a rich source for him. His first writings,the poems of The Red Heart and the stories eventually collected up in The Box Social and Other Stories, were apostate—there was a time when he was writing in unfaith, and troubled by what he has called “the flood of bitter ink/ Flowing from the divided boy long ago,” the boy whose parents divorced11 and the family annexed an uncongenial stepfather—but he returned to the Bible as a source of archetypal stories, and as a comprehensive pattern that stretches from Genesis to Revelation, alpha to omega, a grid, if you like, that answered a growing need in him for large, containing pattern.

Large pattern was one of the things Reaney also took from Northrop Frye, first from Fearful Symmetry, Frye’s book on the poetry of William Blake, and then from the giant Anatomy of Criticism, a book that grew out of Frye’s lectures on literary symbolism in a course that Reaney took in his U of T Ph.D. programme.

Reaney was already a writer when he came under the influence of Frye, but he felt he had been flailing for want of sustaining grid, and needed guidance. The study of literature at The U of T when he was there as an undergraduate was committed to the history of ideas, a thematic approach to literature that he found discouraging. In an essay that pays tribute to Frye as mentor, he says “what a torture to a would-be poet the whole problem of ‘ideas’ and ‘philosophy’ can be. Here I was, at the end of my freshman year with notebooks filled with metaphors . . . but what I wanted to know was [here comes the grid]—what backbones and what galaxies do these lists belong to and in. . . . Already I was conscious of needing the patterns for longer poems than lyrics.”12

There is huge and shapely pattern in Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism. In his third essay, for example, Frye divides the types of literature into four modes: the mythos of spring: Comedy; the mythos of Summer: Romance; the mythos of Autumn, Tragedy; the mythos of Winter: Irony or Satire. These are not watertight compartments; they leak into one another. But they offer a grid into which any work of literature may be placed by those who wish to do so. This kind of synoptic mapping of the “verbal universe” was heartening to Reaney. In a sense, it underwrote everything he did from then on in. However, in looking at what he actually wrote, other than the essays, you would most likely not detect any literal adaptation. Except maybe once, in a loosely-structured dramatic show called Souwesto!

This was presented in the Drama Workshop by student amateurs. One segment of thatvariety show whirligig was a clock drawn right out of Anatomy of Criticism. The minute hand was an actor who revolved with arm and finger pointing by turns at four other actors at north, east, south and west, each of them representing a Frye mode and briefly displaying an action appropriate to the spirit of comedy, romance, tragedy or irony. The tragedian stands out in my memory: every time the dial struck him he doubled over and screamed in pain. Round and round turned the wheel of modes in one of the most hilarious scenes I’ve ever witnessed in the theatre. I’m sure I would have found it so even if I didn’t know I was watching, in fast-forward capsule form, “Archetypal Criticism: Theory of Myth,” third Essay in Anatomy of Criticism.

Two things arise from my thinking about Frye and Reaney:

1) “I’ve sold my soul to Northrop Frye,” said Reaney in an English 138 lecture. Well, there was one genius employing hyperbole to pay homage to another. Of course others have taken that kind of remark as an admission that Reaney was a derivative writer, one of the “Frygians,” or “small Frye,” like Jay Macpherson. Reaney calls these dismissive antagonists “the anti-symbol, anti-anagogy gang.”13 But I’m with Margaret Atwood on Reaney the so-called Frygian. Greeting the publication of Reaney’s collected poems, she says “that most commentators—including Reaney himself, and his editor and critics—are somewhat off-target about the much-discussed influence of Frye on his work. I have long entertained a private vision of Frye reading through Reaney while muttering ‘What have I wrought’ or ‘This is not what I meant, at all.’ And this collection confirms it. . . . The influence of Frye . . . was probably a catalyst for Reaney rather than a new ingredient. . . .14

Amen. Frye came up immediately when I thought to follow Reaney’s gridding, and Frye does have to be mentioned, but no, the sources of much of the gridding lie elsewhere, and are myriad, complex and often interlinked. Grids are everywhere, sometimes left as lists to be later annotated or fleshed out or to become a backbone or “secret structure” for a fully-formed work.

2) Defending his push for native drama and nationalism in general, Reaney says “I don’t believe you can really be world, or unprovincial or whatever until you’re sunk your claws into a very locally coloured tree trunk and scratched your way through to universality.”15 That local tree trunk is not only Souwesto; it’s also highly particular and detailed knowledge of fact and event drawn from widely scattered areas, set into tensile relationship and urged into motion to make what Reaney called “a complex web of little and big sounds.”16 The local particulars don’t come out of Frye. Neither does the poetry.

As I read though The Donnellys again, one thing that stood out in very high relief was its many different aural registers, the sounds made both by props and by actors’ voices, the latter including songs, poetry, animal noises, Latin liturgy, formal or demotic speech of many sorts, English with Irish rhythms and diction, stage Irish, ignorant speech, elegant and witty speech, sophisticated rhetoric, salty language, creative cursing, a showman’s spiel, narrative addressed to the audience, litanies of place names (to carry a character from town to town) and dates (counting off days of the week, months of a year, years of a life—compact expressions of passing time and also, as “a ghost lady” puts it, “another deep down dead leaf self of Mrs. Donnelly crossing times & places as I please/ past life, past death!”17; passages from letters, inquest voices, choral speech and sound effect, newspaper headlines and period prose, items on bills, trial transcripts, legal language, et cetera. Such a list—partial and “dehydrated”18 —may suggest the manyness of the technique, but it says nothing about what was seen as well as heard, nothing about how everything is economically layered together, myth and documentary, voices and bodies, humour and pathos, scene dissolving into tightly woven scene, all gorgeously designed. The list of humble props at the beginning of 14 Barrels From Sea to Sea is a page long. It’s a marvel that, despite the extraordinary complexity, the story line is kept perfectly clear.

During the Winnipeg stand of the national tour, Reaney says he was excited to meet “two separate families whose ancestors had come west from Biddulph township in the nineteenth century.” He had found references to those ancestors during his seven years of Donnelly research. Now, meeting those families, he says “the verbal universe dissolves into human figures and faces telling me things that enable me to go back into the patterns I am weaving in the world of words and adjust here, shade more there.”19 Those shadings, some of them minute, set The Donnellys apart from and, to my mind, above all of Reaney’s other drama. I don’t sell that other drama short—in fact the later comedy, Gyroscope, is one of my favourite Reaney plays—I merely register how very far Reaney has pushed all the levels of his art in creating his masterpiece.

Something else: in many of his other plays antagonists are quite sharply defined: good guys and bad guys, so to speak. Stark black-and-whiteness fits the mythic that Reaney so loves. But the Donnelly family is mixed. Mother and father and son Will, in their different ways, though not perfect, are nevertheless memorably noble, “part of the indomitable spirit of man in all ages,” James Noonan says,”20 but some of the other six boys are too energetic and wild for the good of the family’s standing in the community, “men filled with verbs,” Reaney calls them,21 and a couple of them, “genuinely bad,”22 make it worse. These plays incorporate some of the plot and character shadings of realism that Reaney was mostly inclined to disdain. (“We live in a fairy tale, not in ‘real-life’ novels!,” he wrote in Souwesto Home, “The Brothers Grimm are right/ Dreiser, Farrell and Zola ain’t!”23 There’s no need to agree with this to hear Reaney asserting a view and an aesthetic he often felt was undervalued and demeaned. But he wasdrawing from the nuancing detail of realism in The Donnellys. He needed it to delve into the story of what he has called “a demonic atrocity alive with all sorts of moral complexities that challenge one’s capacity to really understand them.”24

Okay, grids. First, poem (u) of an alphabet of poems in Souwesto Home called “Brushstrokes Decorating a Fan”:

A Useful List:

Hermes

Hera

Apollo

Zeus

Venus

Vulcan

Mars

Athena

Vesta

Hades

Poseidon

Ceres.

Useful for what?

Well, I don’t quite know yet,

But I swear that as an infant,

Born near the Little Lakes,

I met them.

Every morning in our house,

Vesta used to light the stove.25

Vesta is the Roman goddess of fire and the hearth. Her name has appeared on Swan Vesta “strike anywhere” matches since 1906.

Performance Poems has what Reaney calls “a refugee from an unfinished suite of mine called Collegiate Olympus in which the poet sees his high-school teachers as the twelve Greek gods. . . .”26 Also the grains—barley, buckwheat, oats and wheat—“ancient & curiously differing seeds/ Each of whose advents changed lives.”27 Then there are the six senses; the parts of speech; the twelve signs of the zodiac, with corresponding animals and parts of the body; “the twenty-seven words that one uses At Home;”28 the sun, the moon and the seven planets; “Professor Sheldon’s list of the various kinds of male body shapes photographed in his Atlas of Man“29: ectomorph, mesomorph and endomorph, with associated psychologies; the conjugation of a verb to backbone a poem, like the one about Granny Crack in Twelve Letters to a Small Town, One-Man Masque and Colours in the Dark; the nine muses; the furies; the graces; the four directions; the four seasons; the four elements (“in fire or flood or field or air where we wander now” says Tom Donnelly of the afterlife of the Donnellys30); the days of the week; the twelve months of the year, also the Indigenous twelve moons; the constellations; heraldic terms for a coat of arms; the four floors of a department store in a poem called “Department Store Jesus;” the Ten Commandments (called “an alphabet;”)31 “phonetic symbols from Pike’s Phonemics arranged in a circle;32 The Ontario Tree Atlas; the Tarot pack; the game of chess; saints days of the church; and, with much else, the book about Elgin County wildflowers that inspired “The Wild Flora of Elgin County,” one of my favourite list poems in Souwesto Home:

On the roadsides & verges, ditches, ponds, & streams

Of Elgin County,

There are more than 100 families of green persons.

So say those wise guides to the Flora of Elgin County

Messrs William G. Stewart & Lorne E. James,

Of St. Thomas well remembered.

E.g., they invite you to meet Miss Buttercup,

Of the Crowfoot family.

She has a brother named “Cursed Crowfoot”

Who lives in a wet ditch at Kipp’s Corners,

Concession V, Yarmouth township.

Miss Buttercup, by the way, lives on a dry clay roadside

And her first name is “Common.”

Relatives are Miss Hepatica Americana,

And the Windflowers who live at Carr’s bridge,

Two miles southeast of Sparta.

Calpa, Miss Marsh Marigold, again at Kipp’s Corners,

Stands in peat in the water of a ditch,

And the Red & White Baneberry girls can poison you–

Over in dry sandy Springwater woods.

Now, William Blake says that plants & trees,

That—in other words—“Flora” are

“Men & women seen from afar.”

So all these plant families are people,

People you should know,

And become more serene & thoughtful

In doing so.33

I’m reminded of Sarah Milroy, writing about David Milne’s “water colours of still water edges in trees, pictures that offer sanctuary from mankind’s modern fall from grace.”34 Sanctuary, like serenity, is a good word for what Reaney was after. It was something he found in the pacific vision of David Willson, leader of the Shaker-like sect called The Children of Peace. Alphabet 9 has an article by Ralph Cunningham about David Willson, who had his Sharon Temple built to a symbolic grid:

The Temple’s square plan symbolized the ideals of unity and justice; Willson is supposed to have said that the square base signified that the Children of Peace meant to deal on the square with all men. The three storeys represented the Trinity. The door in the centre of each side, at the cardinal points of the compass, indicated that the people were to enter from every direction, and on an equal footing. The equal number of windows in each side were to let the light of the gospel fall equally on all assembled. The lanterns at the corners of the three storeys represented the Twelve Apostles. Inscribed with the word peace, the golden copper ball suspended among the topmost lanterns proclaimed peace to the world. Inside, the twelve columns forming a large square under the base of the second storey stood for the Twelve Apostles. The four columns forming a small square in the very centre stood for faith, hope, love and charity, the foundations on which the Temple was built. Arches linking the four columns represented the rainbow.

For one section of Canada Dash, Canada Dot, a play built on lists of Canadian things, humble and otherwise (as is another play, Names & Nicknames), Reaney draws on this information, adding a few things. The rainbow is Noah’s, he says, and he mentions the 3,000 panes of glass that bring all the light in. “Willson and the sect attract me,” he says in the notes about contributors to Alphabet 9, “because in an era of so much fundamentalist squalor of the spirit, we find a group which has that priceless gift—sensibility—they are like a serene hallucination in the pioneer history of Ontario.”35

One way to approach all the Reaney grid work is to follow him championing traditional education programmes against the so-called “progressive education” that infiltrated educational institutions at all levels during his time as artist and educator. The conflict between traditional and progressive education shows up again and again, in Reaney’s essays, in children’s plays like Geography Match andIgnoramus(the good Dr. History there opposes a Dr. Progressaurus, whose very name says what Reaney thinks of hisapproach), in the long poem, Imprecations: The Art of Swearing, and in my favourite source, Reaney’s first long poem, A Suit of Nettles. The general principle lies in what Granny Delahay says in Reaney’s novel, Take the Big Picture. Granny enjoys being stretched by a story with some mystery to it: “things should be over people’s head,” she says, “or how in Tophet are their heads going to get any higher.”36 It will be no surprise, then, that Granny is also down on an educational outrage that Reaney returns to in several different works, “stunting children’s minds with Dick, Jane, and Puff pap.”37 She is referring to early readers featuring two kids: Dick and Jane, and their pets, Spot the dog and Puff the cat. I remember meeting those flat, insipid characters in school. Having learned to read before I went to school, I could already handle sentences rather more complex and interesting than “See Spot run.”

Before I get to A Suit of Nettles, let me turn back to an illustrative parable at the beginning of Reaney’s tribute to Northrop Frye: “Northerners up here in Canada,” he says, “keep hearing a story about the rock star Jerry Lee Lewis; it is said that his career started when his father brought him home a piano, told him it was his and, not being able to afford lessons, also showed him where middle C was.”38 That story was probably told to illustrate a marvel: no lessons and yet look what Jerry Lee Lewis could eventually thump out on that piano. But Reaney is not so impressed. “Now suppose,” he goes on, “there had been someone present who was not only able to show Jerry Lee Lewis where middle C was, but, instead of leaving the boy to his own devices, had proceeded to show him all of Middle C’s relations, enharmonic aunts and uncles, the twelve families of twelve, etc., in short—the road to the Well-Tempered Clavier?”39 Theory proper to the discipline, in other words—just what Reaney is about to go on and say, in this essay, that Frye offered him. But Jamie, I have to say, The Well-Tempered Clavier is a hell of a piece, but does anybody dance to it? If Jerry Lee Lewis goes the way of Johann Sebastian Bach, what about “Whole Lotta Shakin Goin On”? What about “Goodness, Gracious, Great Balls of Fire.”

I am being serious—somewhat—but I also give Jamie his analogy. After all, this is the Reaney talking who followed the Toronto Conservatory program of piano lessons to Grade Eleven, became proficient enough to play duets with composer and collaborator John Beckwith. It’s the Reaney who sits at a piano to be recorded for an OISE tape on which he plays an assortment of keyboard pieces—hymns, ragtime, classical—between selections of his poems from The Red Heart to Colours in the Dark, and who worked with Beckwith on a children’s musical about competing bands called All the Bees and All the Keys. It’s the Reaney who incorporated music of all sorts into his plays and wrote librettos for operas. He had, and he used, the bones of musical theory and practice—that grid—before he got the Frye grid for literature. What he wanted for his literary compositions would not be quite right for most of your rock n roll composers, and I suppose Reaney’s missionary thrust should be acknowledged. He was a man of great generosity and dedicated outreach. He wanted better for everybody, and he created the shape of that better, naturally enough, in his own image.

A Suit of Nettles is a long-poem beast fable about geese in a Souwesto farmyard. It’s in twelve sections, one for each month of the year. It’s also an extraordinarily sophisticated sampler of poetic forms, grid after grid after grid—too much gridding to lay out here, all of it handled with a firm and gentle touch, some of it quite funny, some of it really poignant. The July section of A Suit of Nettles features an exchange between two geese. Anser is current master of the gosling school. He has the name of his genus, grey goose. He is what he is, and no more. Valancy is named after Isabella Valancy Crawford, one of Reaney’s favourite early Canadian poets. Names usually tell you something in a Reaney poem or play. Remembering the very demanding curriculum of a previous gosling generation, under a disciplinarian called Old Strictus, Valancy says he “taught us to know the most wonderful list of things. You could play games with it; whenever you were bored or miserable what he had taught you was like a marvellous deck of cards in your head that you could shuffle through and turn over into various combinations with endless delight.”40

“Well, well, well,” says Anser,” Might I ask just what this reviving curriculum was.” Valancy’s response is a poem, a litany of grids. It brings us back to the New Jerusalem, with details from the book of Revelation, Chapter 21:

Who are the children of the glacier and the earth?

Esker and hogsback, drumlin and kame.

What are the four elements and the seven colours,

The ten forms of fire and the twelve tribes of Israel?

The eight winds and the hundred kinds of clouds,

All of Jesse’s stem and the various ranks of angels?

The Nine Worthies and the Labours of Hercules,

The sisters of Emily Brontë, the names of Milton’s wives?

The Kings of England and Scotland with their Queens,

The names of all those hanged on the trees of law

Since this province first cut up trees into gallows.

What are the stones that support new Jerusalem’s wall?

Jasper and sapphire, chalcedony, emerald,

Sard, sardius, chrysolite, beryl, topaz,

Chrysoprasus, hyacinthine and amethyst.41

Those various ranks of angels, from Seraphim down to plain old angels, are listed in Performance Poems.42 The Kings of Britain “ (and the Queens), “a tentative list drawn from Milton and Spenser,”43 appear in a section of Alphabet2 called “Icons.” “The influence of the Brontës on [Listen to the Wind] is pronounced.44 And so on.

About Valancy’s programme, really a tight version of Reaney’s own, Anser exclaims, “My goodness, how useless so far as the actual living of life is concerned. Why we have simplicity itself compared to what that maze of obscurity was. I mean since our heads are going to be chopped off anyhow we only teach the young gosling what he likes.”45 Now there’s a defeatist attitude; there’s a diminishing, disheartening dead-end. I regret to say I feel it pulling at me in this Anthropocene era of climate crisis. I’ve lately found myself heartened by Reaney’s example of creative activism, with its roots deep in traditionand his devotion to “world[s] where the laws of atheism, progress and materialism suddenly break down. Surely it is a good thing that they do break down occasionally,” he says, “to let in some terror and some mystery . . . a feeling of there being more depths and heights to our existence than our present-day usually discovers.”46

The grids that Reaney finds to use for either content or form are drawn from disciplines wide-spread, some traditional and archetypal, some particular and local. He was always drawing on what he called “the imaginative force which sees ways of making more meaning out of the world, finding the clue that joins up the different mazelike levels of our inner and outer worlds.”47 The finding brings sometimes obscure or arcane knowledge into the reader or viewer’s ken, information that thickens up the texture of poem or play or essay until the scope of the whole Reaney works comes to seem enormous. Just one more list, this one from Taptoo!,an opera collaboration with John Beckwith “based on events surrounding the town of York, Upper Canada (now Toronto) . . . 1780 to 1810,”48 and featuring various military operations. Scene three is called “How to Play the Drum.” In it, a boy named Seth Harple, whoseparents are Quakers, is undergoing instruction. When he masters his long roll, the Drum Major urges him on as follows: “Well, now then, today, now that we’ve learnt the Roll! The Open Flam! The Ten-Stroke Roll! The Close Flam from Hand to Hand! The Drag! The Drag and Stroke! Let’s try the Eleven-Stroke Roll!”49

I never saw Taptoo!, but I found even reading those words exciting. The discipline-specific terminology shows how Reaney’s research hauls up specific grid information that is both instructive and dramatically potent. This particular research also helped with his play, Wacousta!, where a stage direction says “All the commands are given by different sequences of drum taps.”50

The passage I just read comes from the “outer world” of percussion that is part of the soundscape of the opera, but the drumming, when mastered, is like other kinds of drumming in many cultures. When Seth knows his language, he can speak with it:

I felt so close to our Commander

There were no written orders.

We drummers and buglers were

extensions of his mind.

We were his voice, his thunderous voice,

commanding, commanding.51

This isalanguage of the “inner world.” “Our inner ear,” Jan Zwicky says, “gives life to the music of the human mind.”52

Now it’s important to note that Reaney never wants his gridding to serve anything rigid. “Half the difficulties we’re in,” he says in 14 Barrels From Sea to Sea, “come not from stupid people, but clever ones who get tangled up in systems. . . .”53 There is the basis for most of his drama—the conflict between loving, far-seeing characters who flex, and those who exclude, demonize, persecute and even murder others who don’t fit into their systems. [E]verything and everyone around [the Donnellys], Reaney says in The Donnelly Documents, were part of a closed society with a closed mythology where the individual meant nothing.”54 It’s the nonconformists that Reaney loves, men and women of the spirit, not the letter, people like Dr. Troyer, in Baldoon, a man of vision, generosity and love, as contrasted with John McTavish’s Scottish protestant grasping and emotional thrift.

Baldoon features contrasting Protestantisms, one free and one oppressive. “As the company enters from the back of the theatre,” goes the first stage direction, “they should be singing Tunkard, Mennonite and Shaker hymns; there should be a great feeling of bells, wind instruments—joy in God, the easy attainment of His light, joy in His creation. This should be a contrast with the more austere, bleak music of the Presbyterian psalm book which we’ll use at the beginning of Act Two.”55 Here is the second verse, or chorus, of “Simple Gifts,” the Shaker hymn that opens Baldoon:

When true simplicity is gain’d

To bow and to bend we shan’t be a-shamed

To turn, turn will be our delight

’Till by turning, turning we come round right.56

“To bow and to bend.” A version of this is sung in Sharon Temple during a service of the Children of Peace in Reaney’s libretto for Serinette, the opera: “While lines of division are so distinctly drawn,/ A Saviour’s absent and he’s gone.”57 Sharon Temple is a lantern of light and openness. The contrasting church in Serinette is St. James’s Cathedral in York, Upper Canada, its windows so narrow, and candles not allowed within, that the choir can’t even see to read their parts.

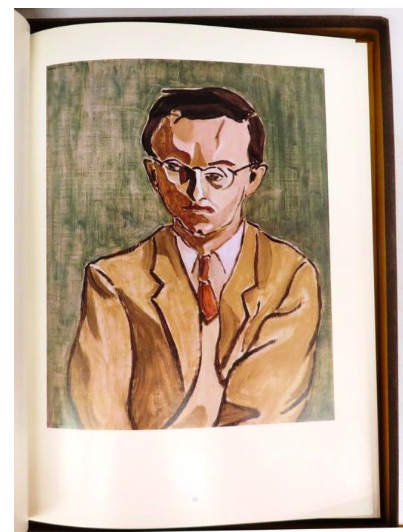

Flexibility of thought and action is a defining feature of James and Judith and Will Donnelly. Tragically, it’s also one thing that their idée fixe neighbours can’t abide about them. Reaney’s Donnellys don’t take sides in local disputes. They are, according to their enemies, renegade be-by-themselves. Perhaps another way to put all this flex is to quote Reaney on the gyroscope which lends the title to one of his best plays. “Gyroscopes,” he says “keep their balance under the most adverse circumstances. . . . if you keep spinning, that is, moving from where and what you are to the opposite of that and then immediately to the opposite of that, then you have power, flexibility, love, energy, community—in short BALANCE—even in our absurd world where the real horizon is often obscured.”58 By turning, turning, we come round right. At its finest, Reaney’s work is what he called “an organism, a pulsating dance in and out of forms. . . ,”59 with, I would add, theory fully subsumed. “The place for theory in the finished work,” says Barker Fairley (who made the portrait of Reaney I showed you first), “is that of the skylark that loses itself in the blue, heard but not seen, forgotten yet flooding the air with melody.”60 I’d say all this organic fluidity was already forming at least as far back as 1962, and is caught in the motto on Reaney’s coat of arms for the Avon River in 12 Letters to a Small Town: “One of my earliest wishes/ ‘To flow like you.’”61

Let me move back into the Donnelly trilogy through the subject of imprisoning grids. There’s a literal grid in a scene early in Sticks & Stones, the first play of the trilogy, which involves a surveyor and the son he has along for company. Preceding the settlers in Biddulph Township, he lays his grid over the township, just as he and his like have gridded world topography. Boy asks father why the people who come to live on Concession Six, Lot Eighteen, eventually to be the Donnelly farm, why they will be fighting over that particular bit of ground. “Well,” the surveyor replies, “to begin with the way this lot is laid out, there’s a small creek enters it from the next farm, crosses it and then flows into the next farm. Farm that is to be. It’ll be the subject of a lawsuit, quarrels about water rights, flooding—they’ll love that little creek.”62

Boy: Couldn’t you stop that?

Surveyor: Well now, what would you suggest?

Boy: Make the farm a different shape?

Surveyor: I’m not allowed to do that, Davie. The laws of geometry are the laws of geometry. No, people must make do with what right angles and Euclid and we surveyors and measurers provide for them.63

Well, the grid of geometry may be the most neutral source of the conflict that eventually overwhelms the Donnellys. The Catholic church is, at first, either neutral or on the Donnelly side. At least the first priests at St. Patrick’s church, Lucan, see the Donnellys as fascinating people, anything but the devils they are already beginning to be made out as. But this changes, partly because the bishop of a later era wishes to use his power to sway the Donnellys to vote conservative, which they never do. The Catholic Church and the McDonald government are in cahoots. So Father Connolly is sent to St. Patrick’s. Connolly is a powerful man, but a man of extremes and little common sense. He visits every family in the Parish shortly after his appointment, first the O’Hallorans, Donnelly enemies and, by superficial standards, the most respectable family in the parish. When he finally reaches a Donnelly household, he already has a fixed sense that they subscribe to none of the values he is supposed to represent, so his visit is confrontational. When Norah Donnelly, wife of Will, says to him “there are always two sides to a story,” his reply is chilling: “Well, Mrs. William Donnelly, in that supposition you are wrong. There is one side, mark this, and one side only.”64 He already knows what side he’s on. He will eventually hound the Donnellys out of his church.

Equally chilling is the self-righteous bishop to whom Will Donnelly addresses himself in a letter, a cry for arbitration between himself and Father Connolly, since priest and parishioner have become rivals in the community. Early in the first play of the trilogy the young Will is being tutored for confirmation by his mother. One of her questions (“would you know . . . how to address the bishop with the proper form of his title. . . ?”)65 goes unanswered. That lapse comes back to haunt in the third play. Here, after reading Will’s letter asking him to “do something before it is too late,” the bishop first has two positive comments: “what beautiful handwriting,” he says, and “The man should have been a priest.”66 But “No,” he concludes, “I am not your reverence, William Donnelly. I am Your Excellency. And. He doesn’t know that before you can stand you must learn to kneel.”67 In his ivory tower high above and remote from the lives of the people whose shepherd he is supposed to be, this bishop has no way of knowing that Donnellys do not kneel, and he has no clue that they are too smart to be taken in by his clumsy strategy to sway them to the conservative side. They are proud, independent, democratic people. They do not submit to those whose vision of things is less complex and tolerant than their own, not even when compromise would smooth their way in life.

One fascinating thing about the shaping of the Donnelly Trilogyis that there is never any doubt about the fate of the family. Their murder is first spoken of, by Mr. Donnelly, early in Act I of Sticks & Stones, and it’s referred to again and again—by Donnellys—before the moment in Handcuffs when the actual massacre happens. The focus throughout is on how such an atrocity, step by isolating step, could come to be. In a sense, the Donnellys are speaking from beyond death from beginning to end of the trilogy. The plays establish that they were living, they are living, they will always be living. “The living must obey the dead,” one of them will say from time to time, often commanding some play-within-the-play about the Black Donnelly story, to show how gothic and unreal it is. The Donnellys havesurvived. They have passed into story false and true, and also mixed, because fiction is shaped differently than history. In The Donnelly Documents: An Ontario VendettaReaney takes 145 pages of nonfiction prose to tell the story another way. The Donnellys have lasted, the trilogy demonstrates, because they were special, charismatic people, and also because of human fascination with the power of vicious darkness that engulfed them.

The massacre is never staged, not directly. It need be represented by nothing more than violent sounds and shadows, because direct narration tells what is happening. And how it is that the victims go clear of the savage brutality of their murders is made clear in the poetic last words of Bridget, the niece whose visit from Ireland was so very poorly timed. She has fled the slaughter going on below: “‘When I got upstairs I went to the window and knelt by it hoping to see a star if the one cloud that covered the whole sky would lift. I knew they would come to get me and they did. They dragged me down the stairs. The star came closer as they beat me with the flail that unhusks your soul. At last I could see the star close by, it was my aunt and uncle’s burning house in Ontario where—and in that house James and Judith and Tom and Bridget Donnelly may be seen walking as in a fiery furnace calmly and happily free at last.’”68

Donnellys may have company in that fiery furnace, just as, In the book of Daniel, Chapter 3, Shadrach, Meschach and Abednego are joined by one other who was not thrust into the furnace by Nebuchadnezzar. The three are “walking in the midst of the fire, and they have no hurt; and the form of the fourth is like the Son of God.” The fiery furnace speech is a beautiful and moving epitome of what Reaney has been reaching for just about all his writing life, reaching for it and trying to spread it—the intelligence of loving spirit that is deepest and best of all the tangle that makes us human. He found that spirit, among other sources, in the Bible, which promises a life beyond death.

So what about The Dance of Death in London, Ontario, a book of poems based on the medieval danse macabre and illustrated with pointillist drawings by fellow London artist Jack Chambers? In the illustration you can clearly see Reaney, poet and professor, holding forth behind a lectern with Death fiddling an accompaniment. Death has the answer to what everyone says and does in the poem, including the poet: you are coming with me. But Death doesn’t have the last word. “Conclusio” sums up the book and ends this way:

‘Death’s Head Moth, King of the Tower of Burs,

With streets and avenues written on your wings,

I shall come to London and join your dancing.

I will be one of your things,

Yet stand not in dread of you,

Thy tumble drum, nor thy hollow fife.

For I know a Holy One who some day will

Shut up thy book with the hands of Life.69

Over the past several months, I’ve been immersed in Reaney’s writing. Some of it has been important to me ever since I first met it, over forty years ago. Some has been new, like the very fascinating Box Social and Other Stories. With some, like Listen to the Windand Imprecations: The Art of Swearing, I have a new and warmer relationship. I’ve also been taking heart from the example of Reaney’s relentless and generous cultural outreach. His optimism and faith, his relentless commitment to community—they help to keep me going. I do struggle to find the BALANCE he calls for, but where I’m all in—heart and belly and mind, all doubts allayed—is with The Donnellys. I place my entire trust in that masterpiece. With its fully-bodied spirit of liveliness and love against narrowness and hatred, The Trilogy holds me. Whether I’m reading it silently or living within it, as I did—dreaming it out70—in the theatre, it’s the Reaney book of Life that shuts up the book of Death for me.

And that is really what I came here to say.

Notes

1. James Reaney, Sticks & Stones: The Donnellys: Part 1, With Scholarly apparatus by James Noonan (Erin, Ontario: Press Porcépic, 1975), 71.

2. James Reaney, “Long Poems.” Long-liners Conference Issue, Open Letter, Sixth Series, Nos. 2-3 (Summer-Fall 1985), 119.

3. Ibid.,117.

4. Quoted in Thomas Gerry, The Emblems of James Reaney(Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 2013), 11.

5. “Long Poems,” 124.

6. “Editorial,”Alphabet1 (1960), 3.

7. 14 Barrels From Sea to Sea (Erin, Ontario: Press Porcépic, 1977), 139-40.

8. Jean McKay, “Colleen Thibaudeau: a Biographical Sketch.” Brick, a journal of reviews 5 (Spring 1979), 10.

9. Guy Birchard, Valedictions: William Hawkins, Ray (“Condo”) Tremblay, Artie Gold(Montreal: Above/ground press, 2019), np.

10. “July: Catalogue Poems,” Performance Poems(Goderich, Ontario: Moonstone Press, 1990), 79.

11. Imprecations: The Art of Swearing(Windsor, Ontario: Black Moss Press, 1984, np.

12. “The Identifier Effect,” The CEA Critic, Vol. 42, No.2 (January 1980) “Identifier Effect,” 27.

13. “Editorial,” Alphabet1, 4.

14. Ibid., 152.

15.“Editorial,” Alphabet4 (June 1962), 3.

16. 14 Barrels, 65.

17. Handcuffs, 138.

18.“Catalogue Poems,” Performance Poems, 81.

19. 14 Barrels, 42.

20. Sticks & Stones, 161.

21. The Donnelly Documents: An Ontario Vendetta, a collection of documents edited and introduced by James C. Reaney (Toronto: The Champlain Society, 2004), lxxxv.

22. James C. Reaney, “Introduction,” The Donnelly Documents: An Vendetta Ontario(Toronto: The Champlain Society, 2004), xvii.

23. Souwesto Home, 60. In an early story called “Memento Mori,” a character called Loyal is a big reader who lives in the books he reads: “Real life! What was that? No, the real life for Loyal was not in the world of things, although he, with book in hand or pocket, managed to help his father on the farm quite well enough; no the real life was in the kingdom of shadows in the small, much thumbed library, and in the mushroom-and-Indian pipes mental landscape that found its nourishment in the chlorophyll of writers, most of them long since dead.” The Box Social and Other Stories (Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 1996), 44. Major John Richardson, author of Wacousta“seems never to have forgotten that reality is only one side of a border river, a river that can expand into lakes as big as seas and takes leaps like thousands of snow white tigers.” “Author’s Notes,” Wacousta!: a Melodrama in three acts with a description of its development in workshops (Toronto and Victoria: Press Porcépic, 1979), 6.

24. “Introduction,” The Donnelly Documents, cxliv.

25. “Brushstrokes Decorating a Fan,” Souwesto Home (London, Ontario: Brick Books, 2008), 22.

26. Performance Poems, 7.

27. Ibid., 25.

28. “The Easter Egg,” Masks of Childhood, edited with an afterword by Brian Parker (Toronto: New Press, 1972), 22.

29. Ibid., 81.

30. Handcuffs, 92.

31. Souwesto Home, 53.

32. Introduction, Gyroscope (Toronto: Playwrights Canada, 1983), np.

33. “The Wild Flora of Elgin County.” Souwesto Home, 33.

34. Sarah Milroy, “David Milne and the First World War” (Canadian Art, Summer 2014), 56.

35. “Contributors,”Alphabet 9, 96.

36. James Reaney, Take the Big Picture (Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 1986), 120. “Given without notes, the Frye lectures in tone rather reminded me at the time of the piano performances of Glenn Gould; a Manitoba friend once remarked that the latter’s way of playing Bach made you “think”; so with the Frye lectures. The energetic drive to clarity makes the listener feel new unused mental muscles swing into action, but never to the point of bafflement. The drive forward is not too clear, but just clear enough. ‘Consequently’ constructions I recall being used a great deal; at the end there was always a paradox that kept you unravelling until the next lecture next week.” “Identifier Effect,” 29.

37. Ibid, 121.

38. “Identifier Effect,” 26.

39. Ibid., 26.

40. A Suit of Nettles, 30.

41. Ibid., 30-31.

42. Performance Poems, 75.

43. Alphabet 2 (July 1961), 92-97.

44. Alvin A. Lee, James Reaney(New York: Twayne Publishers, 1968), 152.

45. A Suit of Nettles, 31.

46. “Author’s Notes,” C.H. Gervais & James Reaney, Baldoon (Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 1976), 119.

47. “Editorial,” Alphabet8 (June 1964), 5.

48. “Taptoo!” Scripts: Librettos for Operas and Other Musical Works. Edited with an introduction by John Beckwith (Toronto: Coach House Press, 2004), 303.

49. Ibid., 313.

50. Wacousta!, 44.

51. Ibid., 314.

52 . Jan Zwicky, The Experience of Meaning(Montreal & Kingston, London, Chicago: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019), 58.

53. 14 Barrels, 105

54. The Donnelly Documents, cv.

55. Baldoon, 1.

56. Ibid, 2.

57. “Serinette,” Scripts: Librettos for Operas and Other Musical Works, 282.

58. “Introduction,” Gyroscope, np.

59. “Preface,” Masks of Childhood, xiii

60. Barker Fairley, Portraits. With a text by the Artist. Edited with an Introduction by Gary Michael Dault (Toronto, New York, London, Sydney, Auckland: Methuen, 1981), xiii.

61. 12 Letters to a Small Town(Toronto: The Ryerson Press, 1962), 3.

62. Sticks & Stones, 46.

63. Ibid., 47.

64. The Donnellys Part III. Handcuffs(Erin, Ontario: Press Porcépic, 1977), 56.

65. Sticks & Stones, 66.

66. Ibid., 79.

67. Ibid., 80.

68. Ibid., 150.

69. James Reaney and Jack Chambers, The Dance of Death in London, Ontario (London: Alphabet Press, 1963), 32.

70. “Art is made by subtracting from reality and letting the viewer imagine or ‘dream it out’, as Owen is told to in the play,” says Reaney in the “Production Notes” for Listen to the Wind. “The simpler art is, the richer it is. Words, gestures, a few rhythm band instruments create a world that turns Cinerama around and makes you the movie projector.” (117)

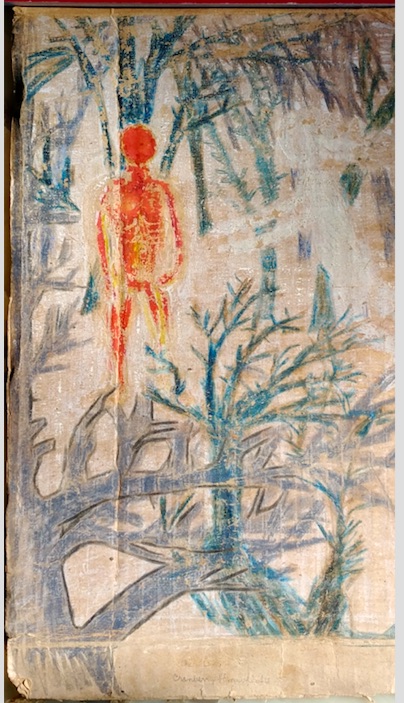

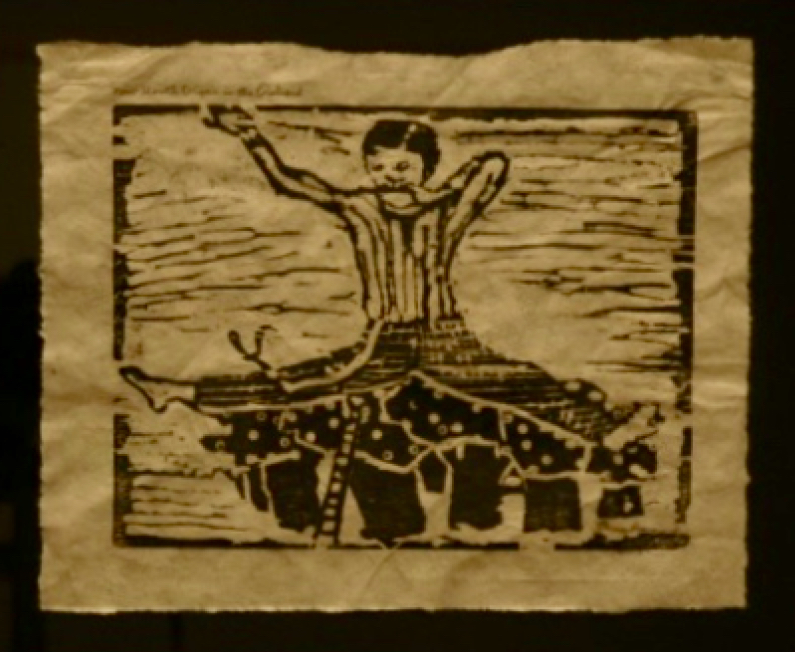

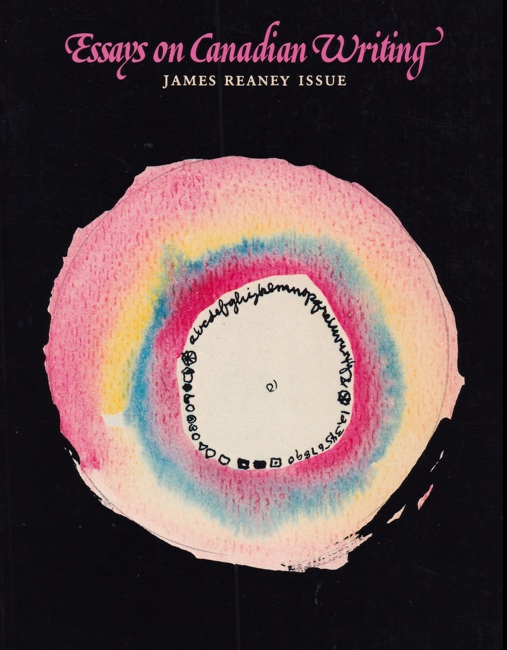

Notes on the illustrations

Here are Stan Dragland’s sources and comments about the images he used in his lecture:

1. Barker Fairley, James Reaney (1958)

“James Reaney I regard as a genius with the unique ability to write innocently about things not innocent.” Barker Fairley, Portraits. With a text by the Artist. Edited with an Introduction by Gary Michael Dault (Toronto, New York, London, Sydney, Auckland: Methuen, 1981), 39

2. Cover, Long-liners Conference Issue, Open Letter, Sixth Series, Nos. 2-3 (Summer-Fall, 1985).

3. James Reaney, George Bowering Deconstructing a Poem by Robert Kroetsch. Open Letter, 232.

4. Alphabet cover: Design by Allan Fleming, later to create the iconic CN logo.

5. James Reaney, “Riddle” (emblem poem: mind, heart and belly)

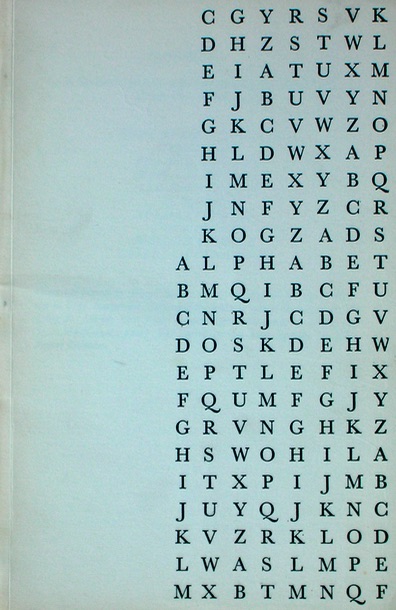

6. Alphabet cover, detail: Once, I don’t remember where, I saw an ad for Alphabet:

Life is B M Q I B C F U

Art is A L P H A B E T

7. bp Nichol, “The Complete Works.” An H in the Heart (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1994), 7.

8. Type case from James Reaney, The Boy With an R in His Hand: A tale of the type-riot at William Lyon Mackenzie’s printing office in1826. Illustrated by Leo Rampen (Erin, Ontario: The Porcupine’s Quill, 1965, 1980), 51.

“There’s freedom and liberty, lad. There’s the mind of man. All his thoughts that thousands of people will read and find helpful—all these in thousands of wee bits of lead stuck together.” (48)

9. Barker Fairley, Northrop Frye (1969)

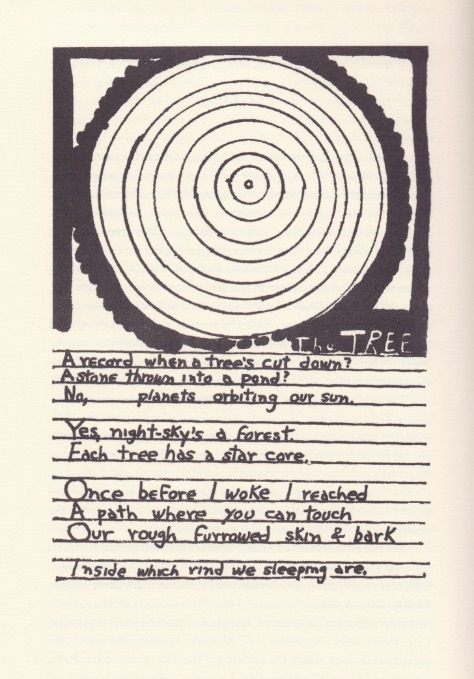

10. “Tree” (emblem Poem)

11. James Reaney, “Rural Dandy” (Self-Portrait). DA, a journal of the printing arts 82 (Spring/Summer, 2018), 2.

12. Vesta ”Strike Anywhere” matches

13. James Reaney, “Near Fraserburg, Fall 1985” (watercolour)

14. Sharon Temple, Sharon, Ontario (now a heritage site)

15. Essays on Canadian Writing, James Reaney Issue

Cover: James Reaney, “From Animated Film,” 1983 (circle includes the alphabet, numbers from 1 to 10, and various symbols)

16. James Reaney, Bicycle with wheels of Queen Anne’s Lace, 12 Letters to a Small Town (Toronto: Ryerson Press, 1962), 33.

17. James Reaney, “New Harmonica in the Orchard” (woodcut)

18. Sharon Temple

19. Stan Dragland, The Bees of the Invisible: Essays on Contemporary English-Canadian Writing (Toronto: Coach House Press, 1991)

Cover: James Reaney, “Cranberry and Snowflake” (gouache and wax crayon—white/black china marker—on cardboard)

20. Jack Chambers and James Reaney, The Dance of Death in London, Ontario (London, Ontario: Alphabet Press, 1963)

(The train in Springbank Park)

21. Dance of Death, “The Poet,” 27.

22. Stan Dragland, ed., Approaches to the Work of James Reaney(Toronto: ECW Press, 1983)

(cover: James Reaney, “Little Donks Bay Near Tobermory,” (1962) (watercolour)