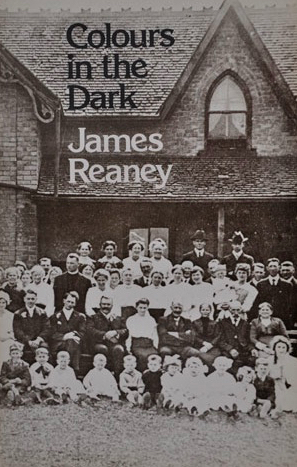

In the 1976 Alumni Gazette (UWO) article “Souwesto Theatre: A Beginning” excerpted here, James Reaney describes the years he spent researching the Biddulph Tragedy of February 4, 1880 and how the knowledge he gained about the Donnellys’ world helped create the Donnelly trilogy.

Orlo Miller, who wrote the historical book The Donnellys Must Die (1962), had based his research on local courthouse documents of the time. Miller’s collection of relevant documents was available to Reaney at the University of Western Ontario’s Regional Archives:

“One of my early experiences back here* […] was to go with my father to hear Orlo Miller lecture at Middlesex College on his recent book The Donnellys Must Die. As a child I had heard the story of this tragic family from our hired man, and my interest was revived now, especially when I heard that Mr. Miller had, in the thirties, collected a huge heap of legal and municipal documents with relevance to the Biddulph Tragedy from the attics of the courthouses at Goderich and at London […]. [In the archives] I entered the really magic world of the past which can only be reached through such fragile ladders and windows as bundles of counterfoils from Sheriff’s cheque books, Court Criers’ Bills, Surveyors’ Notebooks, Chattel Mortgages (whole inventories of people’s furniture and beasts and implements), Jury Lists, Assessment Rules, Crown Attorney Letterbooks and, last of all, mountains of blue paper containing an endless stream of Information and Complaint – the term used for the form you had to fill out when some fellow pioneer had dogged your cattle, tried to pour boiling water on you, torn down your fence, milked your cow furtively or torn down your house with you inside. [Alumni Gazette 1976, pages 14-15]

One of my first research lessons was to train myself to read nineteenth century handwriting and abbreviations; for example, for about a year I somehow assumed that “Inft” meant “infant” so that when you read “.… and poured boiling water over the Inft” I naturally saw the very darkest picture imaginable; suddenly one day it dawned on me that the early Huron District backwoods scene was indeed horrible, but that “Inft” did at least stand for an Informant fifty years old and perfectly capable of running away! Now these documents where a Plaintiff accuses a Defendant of doing something are extremely dramatic, partly because of the variety of things accused, and I made them into one of the choral passages in Sticks and Stones (Part One) in order to show the social situation at its tumultuous litigious mad worst, which is always the dramatic best! [.…] Propelled by the magnetic names “Donnelly” and “Biddulph” I read all the Huron District and County Archives from the beginning to 1863 when Biddulph Township leaves Huron County; I knew that I wanted to write a play about these people, but I wanted to get inside their world first and those hundreds of boxes filled with blue paper – it gets white about 1870 – were the keys to this state. Whoever filed away things in the Huron County Courthouse filed away everything, and I am eternally grateful […]. [H]ere you often get pictures of whole families talking at each other in a way that no history book ever thinks of showing you: one of my favourite lines from the trilogy – “It’s not enough that we should starve, but we must freeze to death as well” – comes right out of a Chancery document. [Alumni Gazette 1976, page 15]

Now there is probably a reason for this material being dear to a dramatist’s heart; a court case is after all a drama – with its lawyers arguing so one-sidedly against each other, with its witnesses opposing each other too and with a Judge, who quite frequently in the early days, climaxes everything with a knock on the head or wallet all around! If at the time you were to have taken a Constable’s Bill to the constable who had just filled it out and told him that it would make a good scene in a play he would have laughed at such foolishness. But time going by changes all that and scholars and artists have as their duty the finding out of just how time does give ordinary things meaning. After the five years were over and I found myself with Five Legal Blue Binders with transcribed material, I found that the three plays of The Donnellys corresponded to three of these binders. All – all!?, I had to do was pare things down from 200 hours of dialogue and action to three hours per binder! [Alumni Gazette 1976, page 15]

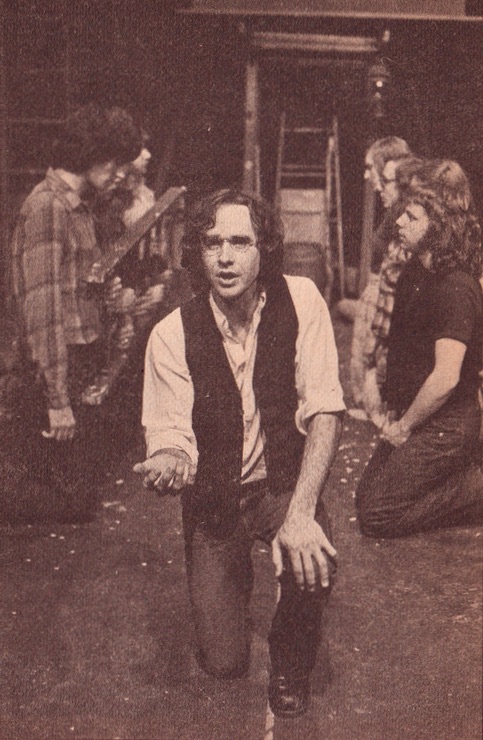

After a series of workshops with my own group, the Listeners, at Alpha Centre and Mini-Theatre, where we used this material in prototypes of the Donnelly plays called “Antler River” and “Sticks and Stones”, I did some more shaping until in 1972 I was invited down to Halifax to work with Keith Turnbull, a former student here on the material using local children and professional actors. The actors wolfed down the contents of the binders – and I think that in their performances you can see that they have genuinely touched some area of time not our own […]. [Alumni Gazette 1976, page 15]

This article originally appeared in Western’s Alumni Gazette in 1976 (pages 14-16). Read the full article here.

For more on James Reaney’s Donnelly research, see The Donnelly Documents: An Ontario Vendetta published by The Champlain Society in 2004.

* In 1960 James Reaney left his first teaching post at the University of Manitoba and came to teach in the Faculty of English at the University of Western Ontario in London, Ontario:

“One of the reasons I decided to leave my first teaching post in Manitoba and come to this campus was that I wanted to find out more about the land of my birth – Southwestern Ontario, or as Greg Curnoe very aptly calls it – Souwesto.” [page 14]

Souwesto history continues to inspire local playwrights: Jeff Culbert has written a one-man musical version The Donnelly Sideshow, Chris Doty restaged The Donnelly Trial in 2006, and Paul Thompson wrote The Outdoor Donnellys (2001) and The Last Donnelly Standing (2016).