As a side note to Leith Peterson’s “Jamie and Jay’s 1965 Apple Butter Collaboration”, here is more about James Reaney’s adaptation of Little Red Riding Hood, one of three marionette plays commissioned by Jay Peterson for the Western Fair in September 1965. Greg Curnoe created the Red Riding Hood marionettes and they are now part of the collection at Museum London. Jack Chambers made a film of the play (Little Red Riding Hood (1965)), which is available from the London Public Library.

Riding Hood pulled no strings in ‘65

By James Stewart Reaney © 2003

(Note: This article originally appeared in The London Free Press, Sunday September 7, 2003, page T6.)

Western Fair in 2003 has goat milking, cooking demos, racing pigs, a world-class Neil Diamond impersonator and much more.

For all that, this year’s fall classic has nothing as subversive as Little Red Riding Hood. In 1965, the fair’s lures included a marionette version of the children’s folk tale – a subversive version.

Subversive? Little Red Riding Hood? Yes, Red, on film, still looks unconventional. Back in the 1960s, a big, bad wolf with U.S. flags for ears and a little H-bomb for company stirred the pot a little. Still does.

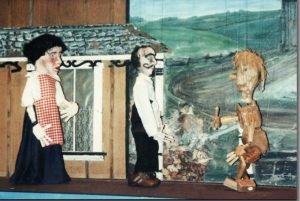

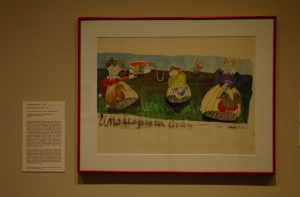

The fair’s Little Red Riding Hood was avant enough to boast marionettes and sets devised by Greg Curnoe, the late London artist. It was Curnoe’s concept to cast the Wolf as a U.S. imperialist predator and use the Vietnam-charged imagery of the day. Red, the wolf and the other marionettes are being donated to Museum London by Curnoe’s wife Shelia. They will be a terrific addition to the collection.

After its run at the fair, Red Riding Hood was filmed by another London artist, the late Jack Chambers. A copy of Chambers film is available on video from the London Public Library. A viewing of Chambers’ simple, direct and beautiful version last week brought back Western Fair memories and showed off Red’s arty side.

The plot is familiar. On her way to grandma’s house, Little Red Riding Hood is lured off the path into the forest. The evil wolf beats Red to granny’s, swallows up the old woman and then devours Red, too. Granny and Red are saved by a valiant huntsman who slays the wolf. Red – and the children in the audience – learn a valuable lesson about sticking to the straight and narrow.

Red was one of three marionette plays developed by my father and others for the 1965 fair. He’s the James Reaney credited as the “story adapter” in the Chambers film.

London writer and archivist Leith Peterson has mentioned the role played by her mother, Jessie (Jay) Peterson, in commissioning Red and other marionette works for the fair.

“Mom saw these shows as not just entertainment for children, but for adults as well. Red Riding Hood caused quite a bit of controversy because of its anti-Vietnam War message,” Peterson has written. Then a Western Fair board member, Jay Peterson was involved in helping create marionettes for other shows.

At the fair, it seemed dad and the others in the Red troupe were battling expectations that marionettes were the glossy creations seen on prime-time TV. Glossy is not the word for the stars of Red. They were really for prime Chambers, not TV.

The Free Press of September 1965 said Red “is another idiom again” – contrasting it with the other marionette plays at the fair. It calls Curnoe “a strong exponent of pop art” and says his “puppets have all been created out of ordinary kitchen utensils.”

As it says in the library catalogue, these Curnoe creations were “unusual marionettes… Red Riding Hood herself is a block of (brightly painted) wood with a red plastic sandpail for a hood and a (plastic) sieve fastened in front for a basket.”

Other characters were assembled from bits and pieces Curnoe had on hand. Granny was “just a teapot” with a teapot lid for a cap because she drank a lot of tea. The kids loved the teapot granny, even if adults saw her as “just a teapot.”

The Chambers film catches Red’s crazy humour. Courtesy of Curnoe, the huntsman had one of those toy guns that make a great rrrrrrr sound when fired. In the film, the huntsman is ready to shoot the buttons off anybody.

In the film’s first five minutes, he fires at a marionette of a hired-man, a character from another of the plays on the bill [Victor Nipchopper from Apple Butter]. The hired man is only there to set the scene and introduce Red’s cast.

Later, the huntsman fires at Red after asking her to put the cake intended for her grandma on her head. The gun-crazy huntsman wonders if she has ever heard of “Wilhelm Tell.” Bang, bang, bang. Rrr, rrr, rrr.

Red is terrified. There is a hole in her hood, she gasps.

“I guess your mother made it oversize,” the huntsman blandly says before pursuing the wolf.

Seeing Red and company at the fair was magical. The young UWO [Western University] types and others pulling the strings were all friendly. John and Gillian Ferns, Chris Faulkner, Jill Bradnock, Ellen Richardson and Alvin Waggener are listed in the film credits. Hearing John’s booming voice and listening to granny singing a Welsh hymn –possibly the voice of his wife, Gillian – recalls an era when town and gown were smaller and closer.

They all worked hard. Red and the other shows were not just a matter of pulling a few strings. Some days, there were four marionette presentations at the Labbatt theatre. Most days, it was hot and noisy. It was never dull on either side of the stage.

Through all that, the collaboration of Curnoe, Chambers and many others endures.

Almost 40 years later, this made-in-London gem is still the best way to see Red.