November 3, 2018 — Thank you all for coming to hear James Stewart Reaney talk about his father James Reaney’s plays for children, Names and Nicknames (1963), Apple Butter (1965), Ignoramus (1966), and Geography Match (1967). As a long-time Londoner and occasional participant in London’s creative community since the 1960s, James shared his memories of the plays and reflected on the influences behind them and the collaborators who helped launch them.

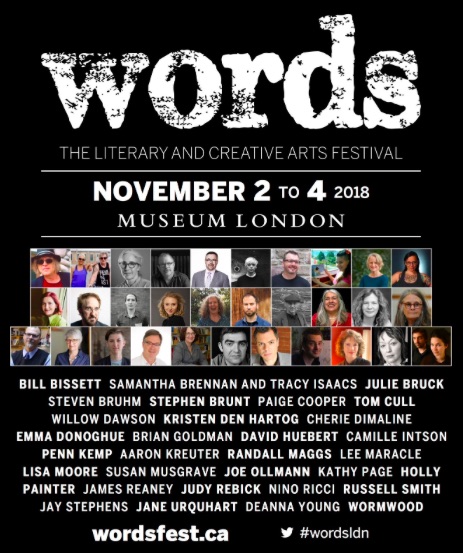

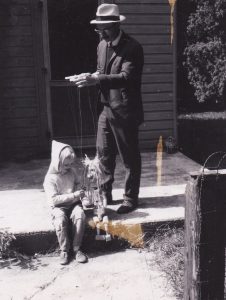

Our thanks to Wordsfest, the London Public Library and Carolyn Doyle for their support, and to Museum London and the Canadian Museum of History for arranging the return visit of the Apple Butter marionettes, Tree Wuzzle and Moo Cow.

James Stewart Reaney’s lecture is reproduced here with permission of the author. (A video of the lecture is available on Vimeo.)

“I Was So Much Older Then: A reconsideration of Jamie Reaney’s Plays for Children … starring Apple Butter, Hilda History, Amelia (Baby One), Tecumseh & many more”.

Thank you for the kind words and thank you all for being here for the 2018 James Reaney Memorial lecture.

I am grateful to the London Public Library and to WordsFest for giving the series a home after a wonderful start in Stratford at the Stratford Public Library. The topic for today is James Reaney’s children’s plays. There are four of them: Apple Butter, Names and Nicknames (which actually came first in a collaboration with John Hirsch), Geography Match and Ignoramus. All are from the 1960s — four years in that decade from 1963 to 1967.

Today’s words are dedicated to the memory of our parents London writers Colleen Thibaudeau and James Crerar (Jamie) Reaney — & to our brother, John Andrew Reaney, who died in 1966.

As I begin, thank you to my wife Susan Wallace and sister Susan Reaney for their tremendous help.

You are free to consider the insights that follow as the third best James Reaney memorial lecture. This is based on my sense that the first lecture — delivered by my mother Colleen Thibaudeau — will always be the best and all the others until now and after this one will be tied for second place.

So for a third place perspective on four plays, I can offer a few insights you will not hear anywhere else and some reflections on plays I first encountered as a preteen or young teenager in the 1960s & then wrote a book about in the 1970s. In more recent times, I’ve occasionally reconsidered the plays & my earlier reactions to them. My 2018 revelations are much less “profound” than they used to be — & likely a lot more fun.

Before sharing the first such insight, some background. I knew it was a hectic, creative time at 276 Huron Street when I was 10 and up in those years. Preparing for this lecture has reminded me, however, how much even an actual witness to history can miss or forget. In addition to the four children’s plays — and the demands of their individual productions — there were other projects, many other projects: in 1963, Dad wrote The Dance of Death In London Ontario in collaboration with London artist Jack Chambers; throughout the sixties he edited Alphabet, a magazine he not only edited but also set its type; and wrote Twelve Letters to a Small Town, a tribute to his home town, Stratford, in collaboration with John Beckwith, Canadian musician and former dean of U of Toronto’s Music School. Twelve Letters was awarded Dad’s third Governor General’s medal.

In 1965, there was more musical collaboration including the libretto for Shivaree, an opera with music by John Beckwith; The Sun & The Moon which premiered in summer theatre here; then Dad’s children’s novel The Boy With An R In His Hand — which this past summer was adapted for the stage at Fanshawe Pioneer Village by Adam Corrigan Holowitz. And can you believe it — there was also a production of Dad’s first play The Killdeer in Glasgow, directed by the late David Williams & with the late Bernard Hopkins in the cast. Dad flew to Glasgow to see his play performed there — and joy of joys, brought me back Manfred Mann’s “If you gotta go, go now” and The Who’s “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” I still play those cherished 45s and think of Dad finding them for me.

Back to Dad’s busy decade. In 1966, Listen to the Wind premiered — as part of an all-Canadian season of summer theatre in London, one year before the Centennial celebrations.

Also in the creative mix was another collaboration with Winnipeg and Stratford theatre director John Hirsch. Colours in the Dark premiered at Stratford in 1967. It shares some of its words with the four children’s plays I am discussing. Martha Henry and Heath Lamberts were in the cast of Colours — I handed out flowers (black-eyed Susans??) at the premiere and wore with pride my Sergeant Pepper red military jacket which I had recently bought in Stratford.

In those creative years, one eye witness memory does stand out. The unique insight I can offer relates to my performance as the mayor of the Munchkins in our grade 8 class’s Wizard of Oz circa 1965. That magic moment is in fact a direct influence on at least two plays I’ll be talking about this afternoon.

My father came away from The Wizard of Oz perhaps overrating the performance of the young Munchkin mayor. He also shared a rueful & amused sense that his favourite child in Oz had been on stage for but a few minutes and that the parents of the four main characters — Dorothy, the Cowardly Lion, the Tin Man & the Scarecrow — had more to be pleased about than he did.

I recall his telling me what he wanted to develop plays in which everyone in the class would be equally involved, more so than they were in what was apparently a very fine Wizard of Oz.

He had already done that with Names and Nicknames — a collaboration with John Hirsch at Winnipeg. But two of the later plays — Geography Match and Ignoramus — are clearly products of the post-Oz approach.

The Mayor of the Munchkins factor may not be as important as I make it. Many of the child actors in Dad’s plays are like players in the works for children’s orchestra written by Carl Orff. In Orff— not Oz — the interplay of simple elements achieves a final complexity that the children would not have accomplished without full cooperation with each other and the director. A similar procedure is followed in these plays for children. A certain world has been created for these child actors illuminated by continual games, chance, improvisational catalogs, and useful character types.

The other unique insight I can offer is that Apple Butter was important to my father very late in his life. We were at dinner with him at Marian Villa — where he spent his last years — when it became apparent that verbal communication wasn’t going to happen.

Instead, for some reason I asked Dad to give his Apple Butter face and he responded instantly with something like this. My mimicry doesn’t do justice to the playful face he conjured up based on the marionette he had created 40 years earlier. The success of the Apple Butter face was followed by two other requests — one for Northrop Frye, a mentor and even a father figure to Dad and the other for Nathan Cohen — a Toronto drama critic who had ridiculed Dad‘s early plays.

The Northrop Frye face was something like this — noble and firm of jaw … a prophet in the glory of his times. When it came to Cohen, Dad twisted his face into a vicious scowl with comically crunched eyebrows.

As a play — not a marionette or a face — Apple Butter is a miniature social and personal history with magic and revenge elements. A child helps the adults mature.

Geography Match expands the mythic framework into a personal vision of Canada. Two groups of children grow as they cross the country.

The strength of family and community is the foundation of Names and Nicknames, a play shaped by word lists from a school speller. Children grow up and prove strong enough to help defeat the evil Nicknamer in their midst.

Ignoramus uses its word lists to satirize theories of education. The children grow from infants to teens — and mature as much as their educational masters allow.

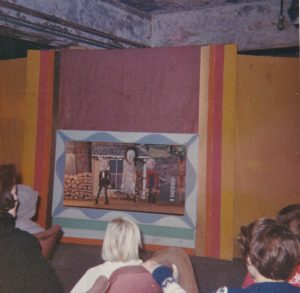

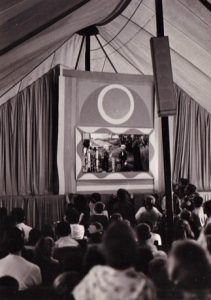

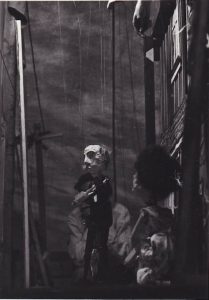

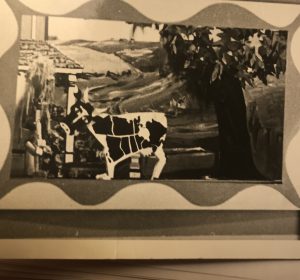

Apple Butter is seen here in its Western Fair glory with a proscenium painted by iconic London artist Jack Chambers & a beautiful set by Perth County artist, archivist and James Reaney cousin James (Jim or Jimmy) Anderson … The marionettes were devised by Dad and Jay Peterson, whose daughter Leith is in the audience today.

The story sets an orphan child alone versus a sinister hired man & brings mythical natural forces to its affectionate presentation of life in Perth County in the 1890s when James Nesbitt Reaney, my father’s father, was a young boy. Quite in keeping with the author’s insistence on simplicity is the rough-hewn appearance of the marionettes. They are all primitively formed creatures of wood, bone and string & not particularly human. Leith wrote the following about her mother’s involvement in Apple Butter:

In his 1990 Theatrum article entitled “Stories on a String,”*[1] Jamie said “…Jay Peterson was a cultural pillar of the town and she persuaded the Fair board to commission a marionette show from me…They actually gave me some money – one third of which went towards a tent, but the rest I salvaged to pay artists and manipulators for designs, puppets, theatre facades, as well as hours of gruelling work rehearsing, learning, and finally for ten days in mid-September, performing from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. on the fairgrounds…Most of the manipulators were my graduate students. We still talk about those very happy, very busy days in the fall of 1965.”

Jamie created Apple Butter, Treewuzzle and Rawbone. My mother made the heads as well as the papier-mache hands for the adult characters. Mom also designed Moo Cow—an impressive-looking bovine, with the map of Canada on one side, built into the Holstein’s black and white markings.

Jamie said that at the Apple Butter production in the Western Fair tent, “babies who cried for everything else shut up for Moo Cow, while backstage visitors enquired after Rawbone with a great deal of respect.”

Apple Butter went on to further acclaim in other locations. After the Woodstock production, Jamie enthused that “children practically accompanied Apple Butter right to the station.”

Victor Nipchopper is Apple Butter’s bitter enemy, and represents a lighter version of the cuckoo bird usurper/villain in The Killdeer, The Easter Egg and Listen to the Wind.

Victor is clumsy and selfish, solely capable of mischief and cruelty, and nearly takes Hester Pinch’s farm for his own. He bullies and dominates Hester and Solomon Spoilrod and effectively prevents their marriage and reconciliation with Apple Butter until MooCow blasts him right out of Perth County and the play.

Indeed, the quaint romance of the spinster and the schoolmaster does bring Apple Butter to a proper conclusion, like most comedies. Marriage is an institution that symbolizes stability and fertility in these works. It is the intervention of the nature spirits that makes possible this social harmony. Rawbone and Tree Wuzzel are sensible guardians for Apple Butter and even manage to temper his joking. They recall characters in folktales, majestic but still approachable, like Treebeard in The Lord of the Rings.

At heart though is the personality of Apple Butter. Robust and good-natured, he is the human character closest to those two natural champions. In the end, he goes off with Wuzzel and Rawbone to find his next adventure.

A mythical version of Perth County (where Dad grew up) is also the setting for Names & Nicknames.

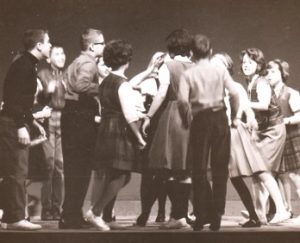

Aside from John Hirsch as director & visionary, & Ken Winters, who composed music for the play, the names that jump out of the cast are those of three members of the first graduating class of the National Theatre School of Canada — Martha Buhs (later Martha Henry) James Langcaster — better known as Heath Lamberts — and Suzanne Grossman, who was in the first production of The Lion In Winter on Broadway in 1966 and became a star in the United States.

While they were rehearsing Names and Nicknames, Martha Henry remembers Jamie sitting there seemingly asleep but she came back “early from lunch one day to find him alone in the rehearsal hall and he was tossing this big doll we had up in the air catching it swinging it around and smashing its head into a wall. I thought maybe I should go and then I realized he wouldn’t care…. John was the boss of course — John and Jamie had known each other for years. John had this curiosity and passion — he would just throw the play up in the air and look at how it fell.”*[2]

A group of children from Hirsch’s children’s theatre including the daughters of conductor Victor Feldbrill formed the chorus. Heath Lamberts told David Ferry: “there was no improv. We would just do what we thought was appropriate but if it wasn’t appropriate John [John Hirsch that is] would tweak…”[3] My father recalled “John would take the work of the actors and would work it in such detail until he’d come up with a fantastic image.*[4]

Names & Nicknames takes place in the pastoral and idyllic community of Brocksden circa 1900.

There is a changeless farm of long ago — Farmer Dell’s — and a timeless school setting.

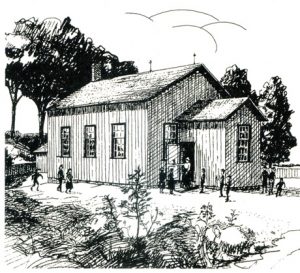

The original for the school was built in 1853 by Scottish settler as well as my great great great grandfather Peter Crerar. It is now a living museum, where groups can learn about the school’s routine back in 1910.

“In 1832, Peter Crerar came from Scotland with his family and claimed land in this area to clear and to farm,” said Gloria Hutchison, the woman who acts as the museum’s schoolmarm (Farmer Dell’s wife is the schoolmarm in the play.)

”During his first winter here in Canada, he didn’t have a house or a barn or anything to sleep in, so history says he found an overturned tree… and he used that hole, perhaps made it bigger, and that’s where he spent his first winter.”

As the story goes, when Crerar’s family came and found him in the spring, they told him his winter shelter looked like a brock’s den — brock being the Irish Celtic and Scottish Gaelic word for badger. In an attempt to retain the area’s history, when Crerar built the first schoolhouse down the road from its current location 13 years later, he called it Brocksden School.

When the children in Names & Nicknames are playing their skipping games or making poems out of their readers they are also creating beautiful wordplay.

However when they are building a snowman, then making the mean-spirited decision to smash it to bits, they are succumbing to destructive impulses: in short, to nickname or to disfigure.

The source of the nicknames is Grandpa Thorntree — a fence viewer and trapper. Thorntree enjoys the pain and confusion of others and is at the height of his power during winter with his traps — rabbit foot not so lucky — while walking freely on snowshoes.

His vicious attacks on the names chosen for infant children means there are 51 unchristened babies in the Brocksden neighbourhood. It is the schoolchildren themselves who are partly at fault for Thorntree’s cruelty (although they sometimes use him as an ally when attacking other kids):

Ha ha Ha. Old Mr. Thorntree

Swallowed a pack of rusty nails

Spits them out and never fails

To make them twice as rusty

To make them twice as rusty

These games arouse Thorntree’s hatred and he becomes a bitter enemy of all children. The old man shows real cunning in toying with the children’s fears and pays nasty attention to youthful uncertainty.

Thorntree’s favourite trick is cursing infants just prior to their baptisms with malicious nicknames. Grandpa Thorntree doesn’t like Paul John Peter James Martin’s proposed name and spits out “Too many names! Fat name!” Paul John Peter James Martin is then called Baby 2, until he can be christened properly.

As Baby 2 he gurgles at Grandpa Thorntree —

Mooly moo dirly irly a doidle.

Two pages later, he proudly joins in the defence of Brocksden and shouts names as dissimilar as Norman and Dionysius (the Greek historian). Adult heroes may struggle for two acts at least In most plays before rejecting evil so wholeheartedly. In Dad’s children’s plays, such wild and optimistic spontaneity is part of the game, and therefore part of the play.

Eventually, a third Dell child is born and christened in spectacular fashion with hundreds of names. The epic list defeats Thorntree & his transformation into an actual thorn tree is the awful miracle Reverend Hackaberry has predicted.

Celebrations of marriage, children and fertility triumph over Grandpa Thorntree’s evil nature. In the end he is revealed to be not human.

On to Geography Match, which has two Nova Scotia schools racing across Canada to Vancouver.

As theatre, Geography Match develops some of the iconography of Listen to the Wind and Names and Nicknames. The stream of blue cloth reappears and so does a ladder. in Geography Match the ladder represents the play’s pair of stairs. A Canadian child fails to climb those stairs and so the Geography Match children must prove that Canadian kids are strong, to satisfy the Governor General of Canada and Prince Philip. This becomes the challenge to the children in their race across Canada.

Kate Collie and Scott Davidson both responded to my request for their memories of performing in Geography Match:

Scott (a friend of my brother John’s) wrote:

I was indeed Squeak Squeak. Remarkably no photos were ever taken as I recall (how times have changed!). My strongest memory is of the tiny toy mouse I carried on stage — barely large enough for spectators in the first row to discern. Important lesson: stage props need to be larger than life!

I fondly remember the “World Premiere” at Middlesex College Theatre in June 1967 followed by a couple of reprises at the Grand over the Christmas holidays later that year. It was a remarkable achievement your father undertook to celebrate Canada’s centennial.

Kate (who lived on the same block on Huron Street as we did) wrote:

Mainly I remember that your dad let us be real actors in real theatres with real responsibilities.

Mainly (also) I remember how he encouraged us to improvise and to let our creativity run free. I composed the recorder music I played but that was minor compared to the music other kids composed and played. He let us create things out of nothing, although it’s probably more accurate to say he (gently) required us to create grown-up things out of nothing.

Lunette (a character in Geography Match) was meek and mild but other characters were grand and fantastical — creatures to be reckoned with. Some part of me is still looking over a shoulder for them in case they’re coming.

Your dad enveloped the whole class with love after John died. The day of the funeral he had us all around the piano at your place as he made up music and songs and kept us singing and laughing. That was Grade 6. We were in Grade 8 (in 1967) when he turned the class into a theatre company. We rehearsed downtown in the Alpha Centre. Then when it was time for a stage, we rehearsed in that theatre at Western.

It was simultaneously serious and a whole lot of fun. I still feel proud of performing at the Grand Theatre. I was 12, having been in some of those mixed-grade classes at Broughdale Public School.

Geography Match ends optimistically with the Canadian child able at last to climb up a pair of stairs. Then the ball of string/spoolknitting pulls in a member of the audience, suggesting that such exploration and discovery is accessible to anyone choosing to travel across Canada.

Speaking of Canada, Ignoramus is another play about the classroom.

Twenty little orphans float into the modern world guided by two bitterly opposed educational theorists Dr. Hilda History and Dr. Charles Progressaurus.

Allan Stratton, London’s successful playwright and novelist now living in Toronto, wrote recently:

How I remember all those plays, and doing AppleButter along with Red Riding Hood at Stratford, in Third Space which is where they used to show off the costumes. I also remember playing the Professor in Ignoramus with Hilary Bates Neary as the other professor. I still whistle ‘Gaudeamus Igitur’.

The initial debate in Ignoramus reaches a forceful conclusion. Hilda History knocks Professor Progressaurus down with her mammoth primary reader in a mock duel.*[5]

The antipathy between Hilda and Charlie (in other words, the Bible versus technology) makes the marriage that ends the other comedies seem unlikely. What would Hilda History and Charlie Progressaurus ever manage to talk about without arguing?

After Hilda‘s victory in the duel, both theorists are unexpectedly given the opportunity to raise 10 orphans each, under the patronage of a wealthy brewer.

Not only do we see first a traditional, then a progressive, educator at work but we also see into their minds.

The location of the two schools provides the setting of the play. Charlie and his kids are unable to cope with Bruce, a classic difficult pupil. They wander around and around their Pelee Island shoreline, getting nowhere until an inspiring pupil named Beatrice intervenes. Beatrice secretly gets her classmates reading — bringing hope to the children in their isolated island classroom laboratory.

For Hilda History and her 10 orphan pupils, the opposite is true. The limitless possibilities of the Prairie Horizon and the night sky imbue the society she is building.

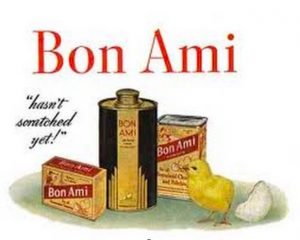

Amazingly enough, the result of the competition is a tie. Beatrice finds religion in the words printed on discarded Bon Ami cans (a kitchen cleanser in powder form). We can complete the litany she devises as follows:

Bon Ami

Polishes as it cleans

makes porcelain gleam

no red hands

hasn’t scratched yet*

*(referring to the newly hatched baby chick in the illustration on the can).

In the final judgment, the charming musician Cynthia compensates for her classmate Steven’s priggishness when Hilda’s students are presented. Beatrice, in her existence poem, says “Love and patience do quite change the scene” — balancing the transistor radio-enforced isolation of Bruce. Shades of today’s smart phones.

Ignoramus doesn’t really end, because Hilda and Charlie are going to switch classes and see what happens next.

The judge of the two educational theories, the Governor General of Canada, speculates that Professor History’s students (who must now suffer for a year with Professor Progessaurus) will change him despite his trendy ignorance. Then one final turn! As the curtain falls, Bruce drops to his knees, acknowledging his ignorance and begging Professor History to teach him to read.

The real victory has already been won, through the faith and imagination of Beatrice. The education of the 18 orphans (one sadly dies in each class) is essentially complete and their minds are ready to bloom.

The four children’s plays offer us marionettes and myths, Canada and community, family and education. To really enjoy them however, we should surrender to our imaginative world, like the four friends at the start of Listen to the Wind. Let’s end this way: We are all children somewhere in Canada thinking about putting on a play.

Copyright James Stewart Reaney, 2018. Reproduced with permission of the author.

Notes:

[1] James Reaney, “Stories on a String”, Theatrum: A Theatre Journal, Issue 18 (April/May 1990), pages 7-8. (See also Leith Peterson’s 2008 article “Jamie and Jay’s 1965 Apple Butter Collaboration”.)

[2] Martha Henry in conversation with David Ferry in 2003, Reaney Days in the West Room: Plays of James Reaney (2009), page 14.

[3] Heath Lamberts in conversation with David Ferry in 2003, Reaney Days in the West Room: Plays of James Reaney (2009), page 14.

[4] James Reaney in conversation with David Ferry in 2002, Reaney Days in the West Room: Plays of James Reaney (2009), page 14.

[5] Dr. Hilda Neatby (1904-1975), who criticized popular notions of progressive education in her 1953 book So Little for the Mind, inspired the character Hilda History. The mock duel in Ignoramus draws on the February 25, 1954 Citizens Forum debate “Education:: The Canadian Controversy” broadcast on CBC Radio.

( ( (o) ) ) HN 1954excerpt

In this audio clip from the 1954 debate, Dr. Neatby points out that the gifted child is not given consideration in modern education.

“Dr. Phillip’s suggestion — if I understood him right — that we must flatten everybody down to a dead level of mediocrity is going to kill our democracy so quickly that we don’t need to worry about the future at all.”

The James Reaney Memorial Lecture series celebrates the life and work of Southwestern Ontario poet and dramatist James Reaney, who was born on a farm near Stratford, Ontario and found a creative home in London, Ontario.