Colleen Thibaudeau: A Biographical Sketch by Jean McKay

from Brick, Issue 5, Winter 1979, pages 6-11.

Reproduced with kind permission of Jean McKay and Stan Dragland.

The following sketch is composed primarily from two interviews with Colleen Thibaudeau, the first, in January 1976, conducted by Stan Dragland, Peggy Dragisic and Don and Jean McKay, and the second in December 1978 with Jean McKay. The interviews themselves each lasted a couple of hours.

The patchwork chart [pages 12 and 13] is the result of a “memory game”. We went through the places where Thibaudeau has lived (the left-hand column, on the chart) and she snapped out quick reactions to the various categories.

PD: How does a poem start?

CT: You generally have a line, comes into your mind, I don’t know from where. Or maybe more than that, even… and if you’re adroit enough to write that down fairly quickly, and its follow-up will come almost right away, then even if you can’t go on with it any more at the moment, if you can get that much down… (this morning, the line hasn’t come yet, but I know the feeling it’s going to be, let me think now, it’s something about calendars, little boxes on calendars being like panes in windows that you can see the day through? Now this morning that sort of came into my mind)… and then the light, it seems to come, either light or music or some movement in the room, or if you’re outside, seems to add another element. I don’t know what that is, I’m just trying to explain it to you. Out of that a line comes. Now, you might change that line, it might have to be longer, or more beats, or different things. And then, if you sit down and work on that, you’re going to have a poem or a story.

Colleen Thibaudeau was born in Toronto on December 29, 1925. Her father, back from the war, was a student at the University of Toronto. He came from the Markdale area of Grey County, Ontario. Her mother was a war bride, from Belfast.

CT: My Dad took us to church, and insisted that we go to Sunday School. My mother only went once, that I knew, and then she hated the smell of the lilies, and never went again. She’s very positive. It was Easter and she asked one of the ushers to open a window, and he wouldn’t, so she said that was that.

When she was a year old, her father took a teaching job in Chesley, a small town back in Grey County. Here her brother John was born. After three years in Chesley, Thibaudeau’s father became Principal of the high school at Flesherton, also in Grey County.

CT: Then in Flesherton the Depression came on, and they were going to have to cut all the salaries in half, and the teachers were so sweet, they were going to give Dad an eighth of their salaries if he’d stay. He did PT too, and he took the debating classes around…

JM: Was he a person with a lot of energy?

CT: I think so, yes, I think he was very energetic. I think he wouldn’t have changed over from being on whatever level he was on there at Chesley to this Principalship even in a tiny little school, except that he felt he would really do something for them, and try to do what had been done for him at Owen Sound. This Owen Sound high school that he went to, I think made people very very… conscientious, and so on. They had very high standards… it’s a Scottish connection up there that’s very high on education… and Dad had wanted to be a journalist, and he had taken part in a lot of debating and so on so it wasn’t hard on him. It was easy for him to train his best kids who were talented, and take them around to debate and they won things. And they were very good in soccer, which is the other thing he was good in.

Rather than stay on in Flesherton, the family moved again to Toronto, where Mr. Thibaudeau (the name is Acadian/French, the Acadian connection being several generations removed) went back to University to improve his degree. The younger daughter Shelia was born there.

Then they moved to St. Thomas, where Thibaudeau attended the last few years of public school, and then high school. Her life in St. Thomas sounds idyllic.

CT: We liked going down to the creek. My mother always let me go to the ravines, because one friend had a police dog, and another friend had a dog… so I think I had a much freer existence probably… we just did everything… We didn’t actually camp overnight because we didn’t have any camping stuff, but we’d go down early in the morning onto these little islands and just stay there and light fires and roast things. That went on for ages, I adored doing that. I never went to Girl Guides or anything like that… We all kept journals, we were all very influenced by Arthur Ransome, that sort of book… running up flags, and signaling, and lookouts, and skating on the river.

During her school days she wrote poems, and some of them were published in Sunday School magazines.

CT: Then the war came, you see, just as I was going into high school. All the extra-curricular activities stopped. Probably if I ever had a chance to got to, say, a literary society, or something like that or a dramatic society it would have helped me a lot ‘cause I would have had to work with other people, you know, the way we did in the Junior Red Cross, you worked together, and you made up your little plays, and so on, and it was quite fun. But there was nothing, see, all the activities stopped because of the war. We had a nice time. We skated, and did First Aid, and I use to work in Gould’s store… just a small town life. There was very little, really, going on. Then the Air Force came, and there were, you know, lots of young men roaming around the streets so you got to know people from all over Canada and Australia.

Thibaudeau’s father’s relatives were still in the Markdale area, and the family sometimes went back there in the summers.

CT: During the war there was gas rationing, so we didn’t go up as much as one would think. The big summer that I remember up there was the summer that my mother went to Ireland, so we had to look after all the kids – my brother and I, and Dad, and my little sister – on what we called “the back place.” There was a house, and some animals, it was next to our bush, and Dad went into the bush with John and fixed up the fences…. I think there was an icebox; I’m not certain, maybe not. I guess we just went every day and got some milk, and kept it around the pump.… My sister had fantastic hair, and it was very hard to keep, and it finally just got beyond me. I couldn’t keep her hair right. She was in the woods all the time, burrs and so on. I tried. I had to do it in three plats instead of two. So my mother just was hysterical when she came back and saw her hair.

From St. Thomas, Thibaudeau went to University College at the University of Toronto.

CT: I was the oldest child, you see, so it was sort of assumed that I could go if I got a scholarship. I wanted to go to UC. My dad had taken me to look at Western, and I didn’t like it. I didn’t like the floors. They were all marbly, and I just wasn’t used to that, it wasn’t like old St. Thomas Collegiate, you know with its nice wooden floors. Stupid.

She received a BA in English, with options in French, and then an MA in English. She met several people who were interested in writing, among them James Reaney, and she contributed both poems and short stories to the student literary magazine, the Undergrad.

CT: I went to the Modern Letters club, which I suppose would be the closest thing to a “literary circle,” but I was the very underperson of that, I would say… My husband never talked very much about writing or anything, he just did it. Phyllis Gotlieb, who was then Phyllis Bloom, was quite a good friend, and Phyllis talked more seriously about doing things. Phyllis was quite confident about what she was going to do. She was already working on certain novels and things, and I never thought in these big terms. I guess I always have thought in fairly small units because I just felt I couldn’t get [larger things] finished, and as long as you keep thinking that way you don’t get them finished, of course.… Henry Kreisel was in that group, and Dorothy Cameron… and Jamie, of course, and Duncan Robertson, Bob Weaver… fascinating people…

JM: Where did you meet Margaret Avison?

CT: I think what happened… Margaret had gone to Victoria College. She knew Northrop Frye, and she wanted very much to meet Jamie. Northrop Frye took Margaret Avison and myself to lunch at Eaton’s College Street, and we had sort of cranberry-like things on blanc-mange, as I remember; you know, it was very nice and light. And the idea was that then I would see that she would meet Jamie. She was so shy that she couldn’t meet everybody all together…. A lot of unexpected things have always happened to me like that, I don’t go looking for them.

DM: One of the stories that you published in the Undergrad, “Wild Turkeys,” seems to be recollecting the Markdale experience.

CT: Well, see, I lived [while at U of T] with my great aunt. Great Aunt Belle was the second sister of my grandmother Stewart.… It was just a pleasure to live with her because she had a slightly easier way of remembering things. My grandma was fun in many ways, but she was just so hurried and harried all the time that she never told you anything. But Aunt Belle was a more gentle easy-going person. And a couple of times, you see, she’d just begin to go into stories like that. So it was from a couple of things she said to me that I reconstructed or made up that story. She wouldn’t have said more than a couple of little hints.

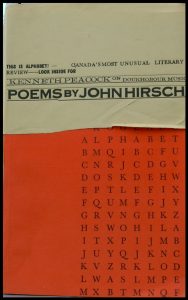

Thibaudeau also had poems in the Northern Review and Here and Now.

SD: Were you at University when Here and Now started up?

CT: Oh yes. It was such a very beautifully designed magazine, that grew out of the Undergrad. You see, Paul Arthur was the Undergrad editor, and very autocratic, and wanted to do everything his own way. He had studied typography and so on with “Graphis” in Switzerland, he’d been in the navy and had gone there before he came back, so that he changed the Undergrad into that gorgeous format, and was very strict about what he put in…. Here and Now started because Arthur was tossed out of the Undergrad, because he was too snobby.

SD: It was quite an impressive magazine.

CT: It’s a lovely magazine, yes. He had contacts from Europe and so on, from his father, I suppose.

SD: Did he know people like A.M. Klein?

CT: Oh yes, he brought the Sitwells over, and did he bring Spencer and Auden? Something like that. They’d be on a circuit, a reading circuit…. Maybe this is a sidetrack, I never knew this man so well, except that he gave me his naval greatcoat when I got married and was going to Winnipeg, he took it off, and he said “you’re going to need this more than I will.” He was funny like that, he was very stuffy in some ways, you know very sort of English, but then he was very spontaneous in other ways….

SD: Was Northern Review going then too?

CT: In ’47 [summer] I worked in Montreal, and that was my first real contact with Northern Review. I’d had a couple of poems in so I phoned them. I didn’t know anybody in Montreal… and they said would you come over tonight, and there was some great to-do about the laundry, I remember…. They had no money, the Sutherlands, John Sutherland, Audrey Aitman. Irving Layton was married to Betty Sutherland who was John’s sister…. Anyway, while I was there (this is terrible, you see I knew very little, I had worked in tobacco and all this stuff, but I didn’t really know how people managed because my mother always managed so well)… while I was there this intricate thing took place, there would be a knocking, so we’d all fall silent and practically hide under the table, in case [the knocker] would be looking through the key hole, and it was that they owed for their laundry… where Audrey who was very very clean took everything, and they would go and pick it up and make some nice little remark and get it away, you see, but it wouldn’t be paid for ages. Everything in the apartment was spotless. She worked nights as a proof reader and so did Betty, but they made so little money, and the men were not working, and they were financing the magazine…. It was very simple…. It was just that summer, I only saw them a few times. John was hand-setting all his magazine.

Thibaudeau completed her MA in 1949, and worked for McClelland and Stewart for a year, doing advertising. Then she spent a year in France, in the town of Angers, teaching and studying. “How to Know the True Prince,” which appears in this issue of Brick, derives from that experience, as do other stories in a planned series that has not yet been completed.

DM: Were there really African Princes in Angers?

CT: Oh yes, that’s not made up. Elements of the story are made up; there was no thievery or anything like that…. The Janine character, I don’t think that was really true, I think that was sort of a friendship, and I made it into a love story. You see, it’s just what is suggested to you by stuff…. There were two African Princes, one was very nice, very above-board, and the other one was very… this white-suited guy that was so different from anybody, and he was involved in some sort of shady dealings, but I don’t think it was exactly what I said. And there were Japanese, and Chinese, and Norwegians… or there had been, other years. People told you about what had been, other years. It was very fertile ground for stories.

In the fall of 1951, back in Toronto, Thibaudeau worked on the Canadian census, and for the post office during the Christmas rush. On December 29, she married James Reaney. They went by train to Winnipeg, where he was teaching English at the University of Manitoba.

JM: Did you feel like you were having a big adventure, going off to Winnipeg?

CT: Oh yes, I loved it…. The only thing that was very difficult about everything – none of the packing or anything like that seemed to be too bad, or the wedding, none of that seemed to be too difficult, although it was very bad weather, but the thing that was the worst, was that Jamie was bound that he was going to teach me how to play chess, and I couldn’t seem to learn…. I wanted to look out the window or do something else.

At first they lived in Reaney’s boarding house, then in a series of apartments. Their first son James Stewart was born while they lived in an apartment on Warsaw Avenue, in 1952. Then for three years they lived in a house in King’s Park, at that time a little German village outside the city. Their second son, John, was born there in 1954. Reaney’s father came to live with them at this time, and remained with them until his death in 1972. They bought a house on Balfour Street in Winnipeg, and were there for another three years.

Thibaudeau was writing and publishing poetry fairly steadily, in a variety of magazines. While she was in Winnipeg she decided to use a pseudonym. She felt that her name was becoming familiar to editors, and she’d like to start fresh. She used the pseudonym pretty consistently from 1951 to 1962.

JM: Did you feel like you were a different persona when you were M. Morris, or was it merely a convenience for publishing? The poems themselves were different, but I wondered if you were writing them as M. Morris.

CT: No, I don’t think I felt any different. The poems were different, I agree, and it made it sort of pleasant to have a different name with them. I just had… problems getting things published and all of a sudden it hit me, let’s put these under different names and see how it goes along…

JM: And it did go along.

CT: It went along much better, and it also sort of separated these ones out, somehow… it’s hard to remember how it felt at the time, but I don’t think it felt like a different persona, actually. I think it was more like, almost like a little house or shelter you built around those, because they weren’t like the others…. I don’t know exactly how I got the idea. It just seemed to come all of a sudden, “OK, let’s try a pseudonym.”

JM: Almost like a prank.

CT: Yes, it didn’t seem to mean very much. Probably that heady atmosphere of Winnipeg makes you think of things like that.

JM: Too much oxygen in your blood.

CT: I had just met this Margaret Morris, who said, “Oh sure, a good idea, I’ll take your mail at my house.”

[In 1956]* the family moved to Toronto while Reaney did his PhD. After two years they returned to Winnipeg, and Susan was born, in 1959. Then, in 1960 they moved to London, where Reaney began teaching at the University of Western Ontario. They lived on Craig Street for a year, and then moved to Huron Street, where they are at present. In 1966 their son John died, from a sudden attack of meningitis.

DM: How do you feel about “the region”?

CT: Around here, it’s a very pastoral sort of region. I used to really miss Grey County…. I don’t think I did like London at first, but now I sort of like it better, and see more in it…. I don’t know whether I feel that [my poems] belong to any particular region or not, really…. I felt really attuned to Vancouver Island, that little region where we were in there [in 1968-69, for a sabbatical year], you know it just felt perfect, and certain other places where we’ve lived I’ve just felt really right in that place, and at some times of the year I feel fine where we live now. Other times, no.

JM: I feel your poems are “domestic” in the sense that you’re not trying to get away from what’s happening to you. They seem to derive quite naturally from the life you lead.

CT: Yes, I’m not a researcher, see, I think you can add a whole new world if you’re a good researcher, and I’ve never really got going at that.

JM: Well, it’s the homogeneity that appeals to me. That’s why I like “The Glass Cupboard” so well, because you’ve got those glasses holding the reflections of everything… all the different worlds really do seem to balance for you.

CT: Yes, they should…. You get energy form using energy, you get more from it, energy to go around faster, and eliminate the things that are unimportant. It’s interesting. We go though different phases, I think. Sometimes you feel as if you don’t have that content within you to express… there’s a sort of bubbling up of the content so that you know you can do it, you don’t know what it is, yet… but you know that that’s there and that you can just keep drawing on whatever it is, endlessly. Well then you go through other periods, where you don’t feel confident that that content exists….

Balancing writing with domestic concerns has indeed been difficult. Nor has sharing living space with another energetically creative individual always been easy.

CT: People were always asking me about the archetypes and things. Well, I never studied the archetypes, and they’re a little bit mentally beyond me, I mean if someone explains it to me I can remember it for awhile, but I can’t work that way. Like he [Reaney] will draw it all out, and he knows from which column he’s drawing his images… and I think that’s good, to be conscious of what you’re doing, but with me they either seem to come instinctively from the right area, or…. It certainly expands your world.

SD: It sounds like your ways of working are different.

CT: Yes, well, I just don’t seem to have the mentality to understand what that is. I understand the net result of what happens to you when you do it, that it expands, and that it also gives you pegs on which to hang your thought. It makes your mind tidier, and so on… but as far as remembering it all, I don’t have that.

I think you have to have a place where you can leave stuff out a little bit. And although we have lots of rooms in our house, we just don’t seem to have that kind of set-up. I usually work on the dining-room table…. I found out long ago that I could not work while he was… fermenting up an idea…. It just created such a whirlwind around the place, that I couldn’t seem to get out of it. Now that is partly just a thing that you feel; if you wanted you could overcome that… but it just seems the intellectual energy or something is just…

JM: Flying around the house.

CT: Yes, and so you can’t always keep your own thoughts straight, you see, and I don’t want to write what he’s thinking, even if I could tap in on it, I would want to continue what I was thinking. I found that very hard. So, poor soul, he goes over a lot to the office.

JM: What do you want a poem to do?

CT: Well… I really would like very much if they were as good as songs… songs that people could hear, and that would be sort of going round in their head…. They’re not, nor is there any music with them, but I was always interested when occasionally someone would set something to music to try and see if it would be a good sort of song…. I like Robert Burns, I like the feelings of those older popular but good, very very good things. I’ve never been able to achieve that, but that’s the ideal sort of thing….

JM: So you want them to belong to people.

CT: Oh yes, if they could. Now the only way they can, is if they’re good enough, and if they really are relevant, or whatever, if the words are right, you know…. And that’s sort of what you’re struggling toward, in one sense…. However you have problems of time and technique, and lack of, what shall we say, getting the thing across properly, or of getting it published, or of this or that, and it’s sort of easier, always, what you do you’ve done because it’s sort of the easy thing you could do at that moment, you see, and it probably isn’t what you were interested in doing.

JM: But it doesn’t make it bad…

CT: No, sometimes if things have that feeling of ease about them, they are very very good…. It isn’t that you want it to last forever.

*Note from Susan Reaney: In September 1956, James Reaney and Colleen Thibaudeau moved to Toronto with their young sons James and John so James Reaney could complete his PhD. (See Colleen Thibaudeau’s playlet “A Nau(gh)tical Afternoon” from August 1956.)